After the invasion of Russian sabotage groups, the situation in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions was so aggravated that it became clear that fighting near Kramatorsk and Sloviansk would be inevitable. Under these conditions, the Ukrainian command tried to amass the forces near those cities. The first units to carry out tasks were special operation forces of the Interior Ministry, the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), and the Armed Forces of Ukraine. The first two were particularly important. It was the special operation forces of the SBU and the Ministry of Internal Affairs that were among the first to fight with the militants and suffer losses. It should be noted that little time had passed since Euromaidan, and the confidence of the security officers to the government, their readiness to perform tasks, and their commitment were rather questionable. To assemble a combat-capable unit faithful to the oath turned out to be a daunting task both in theory and in practice. Special operation forces had come from all over Ukraine. While the army was being mobilised and trying to flex its weakened muscles in anticipation of the opponent, the Ministry of Internal Affairs played an important role. There were so few resources that some special operations—such as guarding checkpoints, checking documents, etc.—were performed by traffic police officers. Step by step, airmobile brigades and the 25th airborne brigade, which were the most capable in the Armed Forces of Ukraine, were deployed outside Sloviansk. The first fiddle was played by the famous 25th separate airborne brigade and the company of the 80th separate airmobile brigade, which moved to Sloviansk from an airport on the outskirts of Luhansk after the Anti-Terrorist Operation (ATO) was launched. Special operation forces of the SBU captured Kramatorsk airport and stayed there until early May, when they were replaced by the 95th separate airmobile brigade.

Pro-Russian forces acted in a rather restrained manner at the time, since there were few of them who had crossed the Russian border—only 52 people. Those had good weapons, ammunition and training, unlike local militants, many of whom in April 2014 stayed at checkpoints with guns or traumatic weapons. Girkin’s group did not attempt to assault Kramatorsk airport, instead using local provocateurs, well aware that the assault would result in the loss of the entire group. Strictly speaking, in terms of combat readiness there was no one in Sloviansk and Kramatorsk besides those 52 armed and relatively trained fighters. It was not until later May and early June when Russian citizens and those who wanted to serve under Girkin’s command started coming there. Therefore, there were fifty well-armed militants and nearly the same number of people with machine guns taken from the Interior Ministry office in Sloviansk and their own weapons—for two cities. In essence, the forces were not large, but they had a silver bullet—significant support from local residents within 10 to 15km around the city that served as informants, and through which the militants could act in advance. The strength of the forces was not enough to occupy and hold the key points on the map, so the enemy relied on mobility and had “nomadic” squads.

The same was with Ukrainian security officials. It was necessary to control not only strategic points and approaches thereto, but also the rear areas (even in Izium of the Kharkiv region, a column of the Armed Forces was shot once) and roads, and maintain order in other cities and villages. To this end, the forces and means of the Interior Ministry and the SBU, and then limited forces of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, were not enough. In addition, a big problem was interaction with and trust in each other. A large number of units that had to be commanded and assigned operational tasks required extraordinary skills on the part of the Ukrainian command, let alone technical support. There were neither skills nor technical support at the time. Therefore, the Ukrainian army, like any other army, had to undergo the trial-and-error period, paying for mistakes with blood.

One of the first units involved in the tasks under Sloviansk after the invasion of Girkin was the 25th airborne brigade. Its paratroopers had a really hard time.

On April 14th, the 25th brigade’s reconnaissance platoon was blocked in the forest near the gas station outside Sloviansk—a complex with filling stations, a service station, and a police station on Highway M03. There were 25 to 28 paratroopers and far less pro-Russian fighters—6 or 7 people under the command of militant Yevgeny Skripnik, call sign Prapor (Warrant Officer). They were detaining them until Sergey Zhurikov, call sign Romashka (Chamomile)—Igor Girkin’s right arm, who commanded the fight outside Semenivka on April 13th—came. According to Russian collaborator Vyacheslav Ponomaryov, the “people’s mayor” of Sloviansk, Zhurikov managed to persuade paratroopers to come to the city for negotiations, after which several of them violated their oath and sided with Russian diversionists. The others were disarmed and allowed to leave. This episode is little studied and rarely mentioned, but it is likely that something of the kind did happen: The SBU reported about it in one of the first radio intercepts from Sloviansk.

The situation was repeated on a much larger scale on April 16th: The enemy seized the armoured vehicles of the 25th separate airborne brigade, with several soldiers and an officer of the brigade siding with the Russians.

The 2nd composite battalion of the 25th separate airborne brigade (which included the units of the 1st airborne battalion, the 3rd airborne battalion, a reconnaissance company, and artillery units) was assigned the task of securing a foothold at Kramatorsk aerodrome (the 1st airborne battalion was near Amvrosiivka at the Russian border at the time). The day before, on April 15th, they received an incomprehensible order to redeploy from the Kharkiv region and Dobropillia, the Donetsk region, in the Dnipropetrovsk region. After completing the march, they got a new task—to arrive at Kramatorsk aerodrome by 5:00pm on April 16th. This was despite the fact that the fighters did not have time to rest, nor bring the equipment to proper condition. In order to facilitate the performance of the task, it was planned to move directly through Kramatorsk, which was already occupied by a small number of enemy forces. The movement through the city should also have been sort of muscle-flexing. Instead, the worst scenario was played out: the armoured equipment of the 25th separate airborne brigade entered the city in small groups and several columns due to malfunctions of the equipment. The full-scale march failed, and the split groups were vulnerable to enemy attacks.

The movement of columns was blocked by civilians. The blocking was well organised, involving dozens of locals in the areas of the movement of the columns, who closely surrounded the armoured vehicles, not allowing them to manoeuvre. Such actions of the locals ended in different ways. In one case, Ukrainian officers were able to demonstrate the seriousness of their intentions to execute the order, clutching grenades with pulled pins in their hands. In other cases, the skills of the drivers saved the day: For example, during the blocking near the railway, one of the armoured vehicles managed to crush the car that was trying to block the way under its tracks, and the entire column—about 24 combat vehicles and self-propelled guns—was able to pass. In all those cases, the actions of Ukrainian paratroopers were professional: None of the civilians were injured. Even in the footage—especially liked by Russian propagandists—where Ukrainian soldiers were allegedly “shooting at civilians,” the video from the scene shows that all civilians remained alive and well.

However, one of the columns experienced much more difficulty in the streets of Kramatorsk. Six armoured vehicles from the 3rd composite battalion of the 25th brigade stopped in Rynkova Street and were blocked. Upon that, the column was surrounded by people from the nearby market, with the crowd running to 300 to 400 people. Soon after that, armed militants appeared among the civilians and began negotiations with the Ukrainian officers. The situation was unfortunate: Had the situation worsened, the Ukrainian soldiers would have been at gunpoint of the militants, while the militants themselves would have been safe among civilians. The Ukrainian officers were approached by militants of different rank, who demanded that they give up their weapons, but each time the Ukrainian side refused. The talks ended not in favour of the Ukrainian military—the militants managed to disarm the commander of the column. According to the report of a Ukrainian paratrooper, published by the SBU, the commander was disarmed by Igor Girkin himself, who had arrived at the scene, wearing a balaclava. The armoured vehicles were seized by the militants, and the paratroopers were taken to a city building, assembled in the hall room and offered to join the Russian side. An officer and several soldiers, most of whom were from the Donetsk or Luhansk region, accepted the offer. Most of the paratroopers did not violate their oath and were given the opportunity to leave the city, threatened that they would be burned if they ever returned. Thus, the Ukrainian forces lost six armoured vehicles—a BMD-1 (No. 813), a BMD-2 (No. 842), three BTR-D (No. 709, No. 815, No. 847), and a 2S9 Nona (No. 914). The officer who betrayed the oath was Senior Lieutenant Yaroslav Anika (call sign Taran (Ram), deputy commander of the company). Some information is known about the defected soldiers and sergeants—Sergeant Havziiev, soldier Sinko, and sniper Rodionov from the 3rd battalion.

As it turned out, the self-propelled guns (Nona) and man-portable air defence systems (MANPADS), left in one of the vehicles, which were seized by the militants, brought about the most destruction. It was this Nona, and later her “twins” from Russia, that took many lives of Ukrainian military.

On April 17th, a tragedy took place: People with the firm pro-Ukrainian position were captured by militants in two different episodes. Five Right Sector activists reached the outskirts of Sloviansk from Kyiv through Kharkiv by themselves, in order to study the situation and “see everything with their own eyes,” their friends explained. The group consisted of 18-year-old Yurii Popravka (call sign Patriot), 25-year-old Yurii Diakovskyi (call sign Kirpich (Brick)), 23-year-old Vitalii Kovalchuk (call sign Volk (Wolf)), and two other people with call signs Mark and Apostol. They had with them only two firearms, most likely sawed-off shotguns (different sources call them pistols, rifles, or sawed-off shotguns) and stun grenades. It should be noted that although Russian propaganda presents Right Sector as kind of a sect with ruthless trained killers, the organisation itself has never been homogeneous—from the outset, it has united very different groups. The same was true in April 2014, so it is not surprising that several activists who associated themselves with Right Sector were only a lightly-armed group of young people acting at their own risk.

Having rested after their trip to Sloviansk, on the evening of April 17th Yurii Popravka, Vitalii Kovalchuk and Apostol went to the checkpoint, where they were noticed by the militants. After a short shootout, the guys just ran away and were chased by the militants. Yurii Popravka lagged behind and was captured. The other four quarrelled and separated: Yurii Diakovskyi decided to come back the way they had come; Vitalii Kovalchuk went to hitch a ride on the road; and Mark and Apostol contacted Right Sector and agreed on the collection point. As a result, both Yurii Diakovskyi and Vitalii Kovalchuk, whose car was stopped by armed people, were also captured by the militants. The three captives were taken to the basement of the SBU building in Sloviansk, where they were shoved and tortured.

Not only Right Sector members were tortured in the basement of the Sloviansk SBU building. On 17 April 2014, Volodymyr Rybak, a deputy of the Horlivka city council, was abducted by people of Igor Bezler right after a rally, where Volodymyr had tried to remove the flag of the “DNR” from the city council building and raise the Ukrainian flag instead. After being abducted, he was taken to Sloviansk and tortured with the others.

Yurii Popravka, Yurii Diakovskyi and Volodymyr Rybak were executed on April 18th, and their truncated bodies were thrown into the river. On April 19th, the bodies of Popravka and Rybak were discovered by local fishermen in Kazennyi Torets River. The body of Diakovskyi was not found until April 25th. Despite the fact that Popravka and Diakovskyi were not well trained, they still had weapons in their hands, and therefore were combatants, that is armed members of one of the parties. Their execution as prisoners of war was the first known war crime in the Donbas war. Volodymyr Rybak became the first civilian killed in this war. It contradicts all Russian efforts to portray militants as heroes who protect civilians.

On April 19th, Dmytro Yarosh and Right Sector received the first means of transport: two Mitsubishi L-200 and two Nissan pickups. There were huge problems with arms, though—they managed to pick up AKSU, AKS, Saiga hunting carbines, two sniper rifles and a Yugoslavian M53 machine gun. The group was tasked with disrupting the transformer of a television tower at Mount Karachun near Sloviansk to limit enemy propaganda on TV. The TV station had been seized on April 17th by militants, who immediately switched off Ukrainian TV channels. It was decided to act at night. The group moved from Dnipropetrovsk late in the evening, and came to Sloviansk at 1:00am. The column was to have pulled off the highway before the city towards Karachun, perhaps through a bridge near Bylbasivka. On the ATO map, the turn was marked as free, with the militant’s checkpoint being two kilometres away. However, another checkpoint had already been erected right after leaving Bylbasivka, and so the column unexpectedly came out directly before the enemy, stopped 50 metres away from the concrete blocks.

The militants immediately opened fire, and practically, the first burst killed Mykhailo Stanislavenko, the driver. In the course of a short battle, the checkpoint was cleared, with five to six militants killed, according to various sources (as of now, the names of only four of the killed are known). The battle, however, was only beginning to enter the active phase. Some militants retreated closer to the city and fired. The enemy’s reinforcements started to arrive. The machine gunner of the enemy focused his attention on the Right Sector cars. Another Right Sector fighter was seriously injured in the battle. 19 fighters along with the wounded one got into two cars and retreated. Unfortunately, Mykhailo Stanislavenko’s body remained on the battlefield. A jeep and a pickup of Right Sector were burned down until next morning. However, before doing so, the militants found Right Sector insignia and printed-out Google maps with the TV tower in Karachun marked on them.

The militants made several statements regarding this incident. They argued that the battle at Bylbasivka had been with Right Sector because they had found their insignia and Dmytro Yarosh’s visiting card at the scene. It caused a whole wave of ridicule on the part of the Ukrainian public at the time, since a visiting card could not have remained intact in a burnt-down car. However, this statement was true: The things had been taken out of the cars before they were burnt down. But there was another statement that was in fact false: The militants claimed that they had caught one of the attackers after the battle on the highway as he tried to leave the area. That man was Vitalii Kovalchuk, who had been captured on April 17th with Yurii Popravka and Yurii Diakovskyi, two days before the shootings outside Bylbasivka.

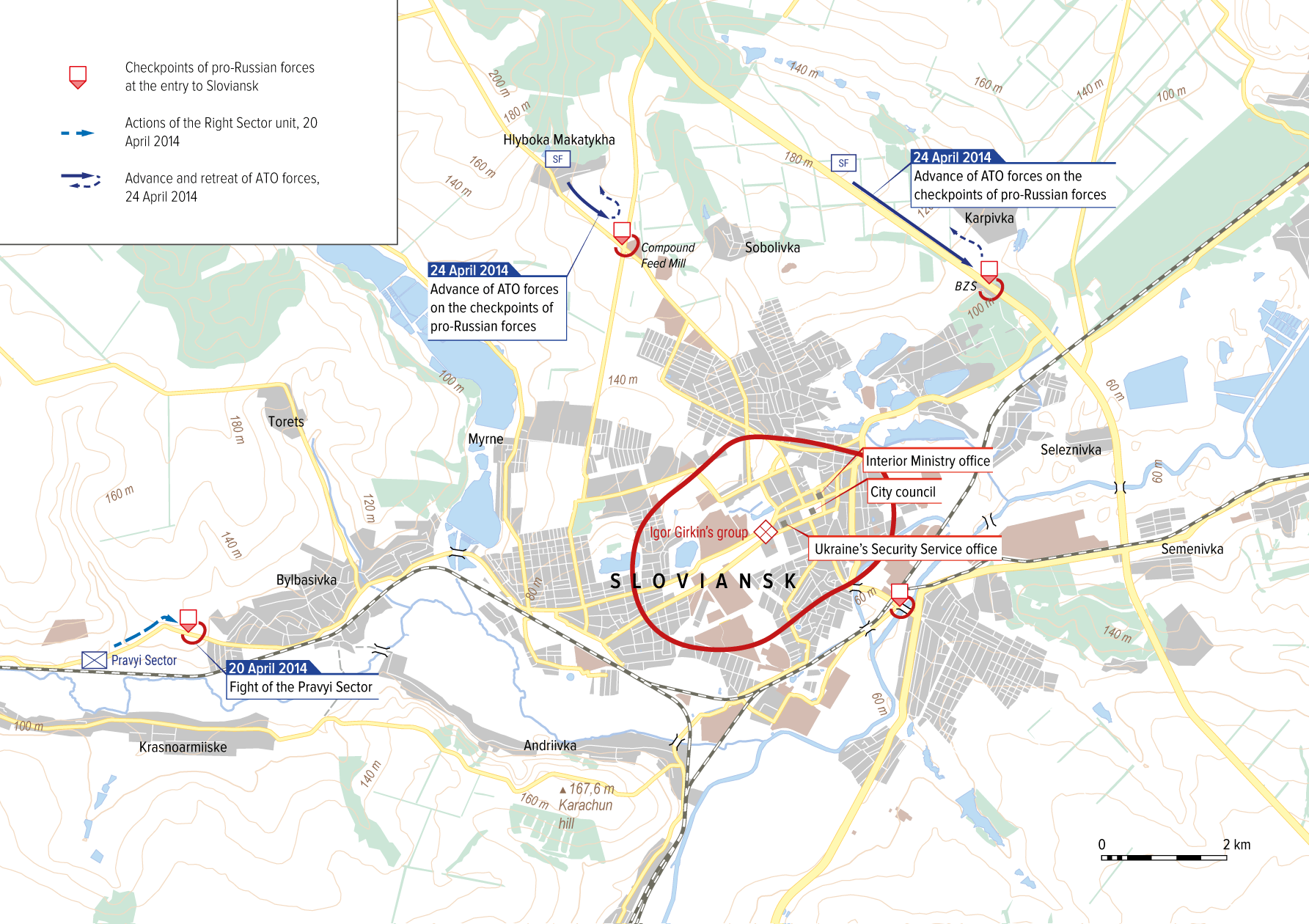

On April 24th, special forces of the National Guard of Ukraine, with the support of several armoured personnel carriers, carried out a trial offensive on one of the fortified checkpoints in the north of Sloviansk, “Compound Feed Mill.” The fighters burnt the tyres and left the checkpoint with little resistance. However, for unknown reasons, the Ukrainian forces did not secure their position there and left—probably due to the lack of personnel, since leaving the special forces to guard the checkpoint almost in the middle of the field was impractical at the time.

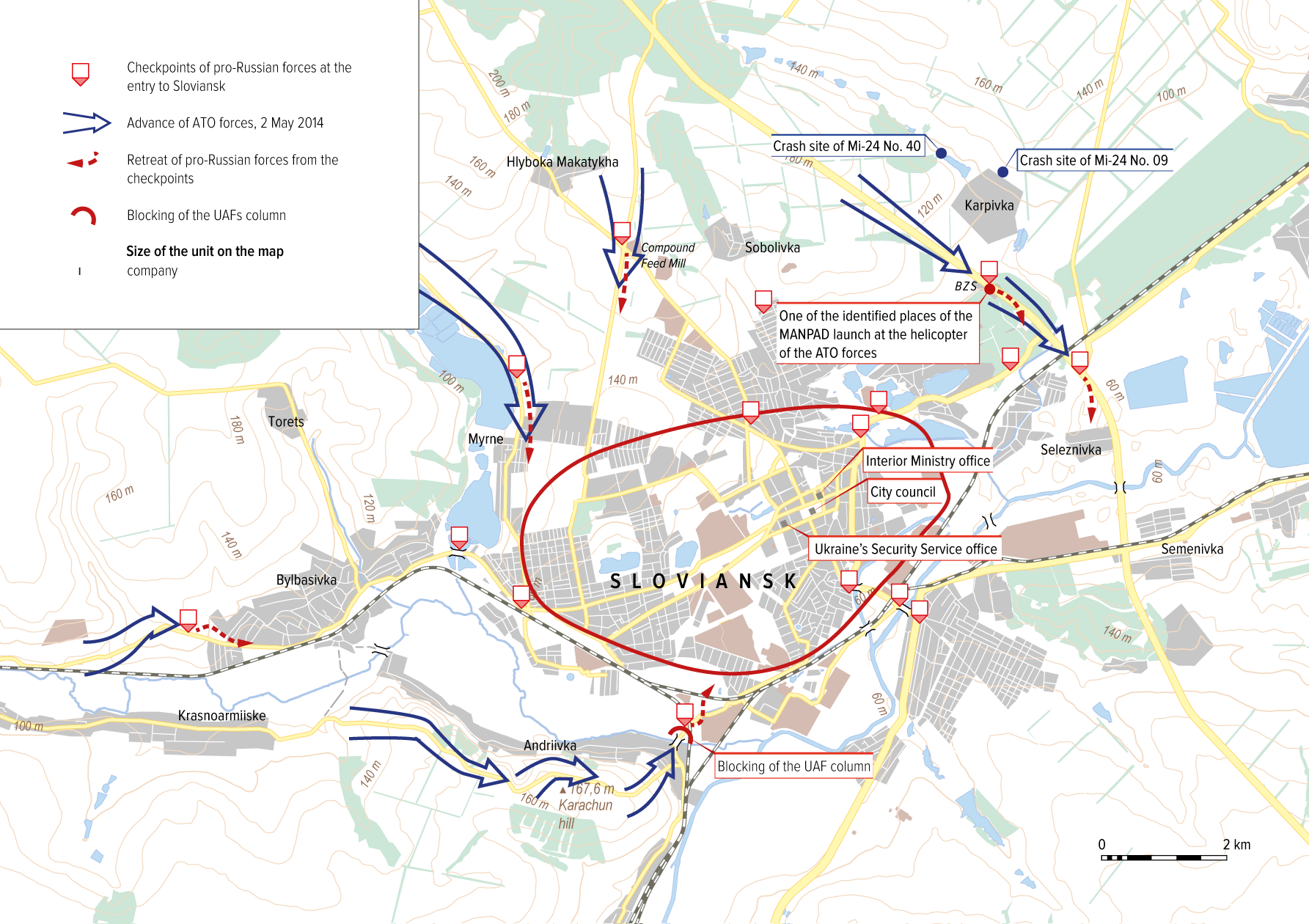

On 2 May 2014, the largest operation of the Ukrainian forces was carried out since the beginning of the armed conflict on April 12th—a number of militants’ checkpoints around Sloviansk were destroyed, and the city was practically surrounded. In early May, according to various sources, there were 160 to 300 militants in Sloviansk, and about 50 in neighbouring Kramatorsk. On that day, the Ukrainian command planned to use two factors—first, its advantage in terms of armoured vehicles and personnel; and second, aviation, namely attack helicopters. The operation was to begin at 4:00am. The exact number of helicopters is unknown, but Russian sources, in particular Igor Girkin, said that about 20 helicopters were seen above Sloviansk on that day. Most likely, it is an exaggeration, but it gives an idea of the significant forces of the army air force involved in the operation.

The Ukrainian forces suffered losses at the very beginning of the operation: Two attack helicopters from the 16th army aviation brigade were shot down. Mi-24P “09 yellow” flew over Sloviansk, tasked with providing support to the Ukrainian columns which were moving towards the city. At around 3:00am the helicopter was flying over Karpivka (a village to the northeast of Sloviansk), at an altitude of approximately 600 metres, when a MANPAD missile was shot and passed it by. A second missile, though, was launched right after, and struck the helicopter. It flamed up, started to spin, fell almost vertically, and crashed near a pond outside Karpivka. The fall of the helicopter was filmed by residents of Sloviansk from a tower block in Svobody Street. The author of the video mistook a flame on the horizon for a signal rocket, but in fact it was a falling helicopter on fire, which exploded immediately after crashing into the ground, with a column of smoke rising from the crashing site. The video has a unique testimony: At the time of the filming, the author was talking with his wife, who was reading forum messages on the Internet; she told her husband that someone has just written about a helicopter shot down supposedly from a “Mukha” (infantry grenade launcher RPG-18). This story became widespread at the time: Russian sources reported that a young militant had miraculously hit the cockpit of the helicopter with a grenade launcher. The possibility cannot be excluded that the helicopter was targeted with grenade launchers, but most likely this whole story is completely made up: The helicopter was at a rather high altitude, and only an anti-aircraft missile could have hit such a quick target. Major Serhii Rudenko and Senior Lieutenant Ihor Hrishyn died in the crash. Only one crew member, Captain Yevhan Krasnokutskyi, was able to jump with a parachute, and was later wounded and captured by the militants. Ihor Hrishyn, by the way, was born in Sloviansk, and died while on a military assignment over his hometown.

Another helicopter, Mi-24P “40 yellow”, moved almost at once to assist the first, but was also hit with MANPADS. It fell in the same area, but somewhat further, in the woods behind Karpivka. The entire crew—Major Ruslan Plohodko, Major Oleksandr Sabada, Captain Mykola Topchii—died.

At the moment, one point from which MANPAD missiles were fired that morning is confirmed—this is BZS. BZS (probably an acronym from the Ukrainian for “gas station”) is a large complex on Highway M03 outside Sloviansk, with refuelling stations, service stations, and a police station, with the whole market and even a small hotel complex nearby. Upon seizing Sloviansk, Russian militants took this complex under control, thus blocking important Highway M03 (Kharkiv—Artemivsk—Debaltseve—Dovzhanskyi—Russia), and set up a checkpoint there. This is where MANPAD missiles were launched on the morning of May 2nd. The video of the fire was given by the militants to Russian correspondents of Komsomolskaya Pravda (The Komsomol Truth)—Alexander Kots and Dmitry Steshyn. The launch site was also identified—a service station for trucks at BZS. The missile was launched roughly towards the area where Ukrainian helicopters were before they crashed; it can be assumed that the video shows how the second helicopter, Mi-24P with the flight number “40 yellow,” was shot.

Despite the losses at the very beginning, the operation continued. Ukrainian forces, which consisted mainly of special units of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (Omega, Vega, Jaguar), as well as some units of the Armed Forces, went out to several checkpoints of the militants outside Sloviansk. They were commanded by National Guard generals Valerii Rudnytskyi and Yurii Allerov. The special forces were moving under armoured protection and managed to seize a number of important checkpoints around the city—at Bylbasivka, Myrne, and Compound Feed Mill; BZS was seized, too. After the operation, the Ukrainian command reported that four MANPAD operators had been detained. There are no details regarding those operators, although the fact of having seized BZS gives reasons to believe that there was at least a chance to capture operators.

On the morning on May 2nd, the paratroopers of the 25th separate airborne brigade cut off the Sloviansk—Kramatorsk highway, setting up checkpoint No. 5. It was located almost under the Sloviansk stela, a kilometre away from the city border. Around 50 paratroopers under the command of Major Tkachuk had six armoured vehicles. At some point, the group was joined by two Alpha fighters, and several SBU officers, who advised the paratroopers on the setting up of the checkpoint.

That morning, Ukrainian forces forced the militants out of the TV tower in Karachun. Russian militants had seized the TV tower on April 17th, and first of all cut off the broadcasting of Ukrainian TV channels and radio stations. On the morning of May 2nd, the tower was guarded by 16 militants, commanded by a militant with call sign Sapsan (Peregrine), according to Russian sources. As the Ukrainian forces approached, the militants fled. Russian sources would subsequently report their account of the reasons for the defeat: When a Ukrainian armoured carrier drove up to the TV tower, the militants tried to hit it with grenade launchers, but three grenade launchers in a row failed.

After seizing Karachun, the Ukrainian column of the 1st battalion of the 95th separate airmobile brigade approached Sloviansk from the south, near the ceramics factory. Mount Karachun and the village of Andriivka on it are separated from Sloviansk by Sukhyi Torets River, which has a highway and a railroad bridge, located close to each other. An improvised barricade of tyres and sandbags was set up behind the highway bridge by pro-Russian forces. As the Ukrainian column approached, the militants set fire to the tyres and fled from the checkpoint. The paratroopers crossed the bridge, entered the checkpoint, but could not continue to move – pro-Russian civilians came from the outskirts of Sloviansk and blocked the movement of the column in both directions. The column itself consisted of about eight armoured personnel carriers and some other vehicles. The civilians were well trained to create a television picture: They pretended to be throwing themselves under the wheels, although, of course, they did not endanger themselves seriously. A number of Russian news media reported that a Ukrainian armoured personnel carrier had allegedly “run over the legs” of an elder man. TASS reported that the pensioner “got under the wheels of an armoured carrier,” calling it the only casualty in the collision. Russian media completely made up the story: Fortunately, AFP footage with this man was included in their video, where he can be seen lying on the grass, and not only without any injuries or fractures, but also with no signs on his clothes that he had got under the wheels. The paratroopers were sent reinforcements—a Mi-8 helicopter landed on the shore of the river between the bridges, bringing reinforcement troops. However, this did not change the situation—the blockade lasted until late evening. Around 10:15pm, a rather dirty provocation took place—militants started shooting to kill at the Ukrainian paratroopers behind the civilians’ backs. Probably they meant to provoke the paratroopers to open fire in response, resulting in mass civilian casualties. The Ukrainian soldiers opened fire in the air, over the heads of civilians, and the column moved back to Karachun. Two paratroopers died—Petro Kovalenko was killed in a VOG grenade blast, and Serhii Panasiuk was shot in his neck. Another seven soldiers were injured and about the same number shell-shocked.

And on this tragic note the day was over. During the battles on May 2nd, an important task was accomplished: The first step was taken to block the city and practically surround it. Several checkpoints of the militants were seized, while the Ukrainian forces set up 18 own checkpoints. The Ukrainian special forces, who carried out the assaults, were immediately followed by volunteers—former Maidan activists from the 1st battalion of the National Guard, which had just been formed in Novi Petrivtsi. They secured the seized checkpoints and subsequently guarded them.

There is precious little information about the militants’ losses on that day. It is only known that, in a “sniper duel,” an Alpha officer killed Sergey Zhurikov, or Romashka (Chamomile)—Girkin’s right hand, who commanded the fighters in the first battle on the morning of April 13th outside Semenivka, and negotiated during the blocking of the 25th brigade. There is every reason to believe that the militants’ losses on that day were bigger since one of the most influential field commanders of the city was killed.

The village of Semenivka near Sloviansk played an extremely important role in communications control—there was an important crossroads there. This was understood both by the Ukrainian command and by the enemy. It was here where, on April 13th, the first battle with Girkin’s militants took place, in which an Alpha officer was killed and the 80th separate airmobile brigade had joined the battle for the first time and covered its comrades.

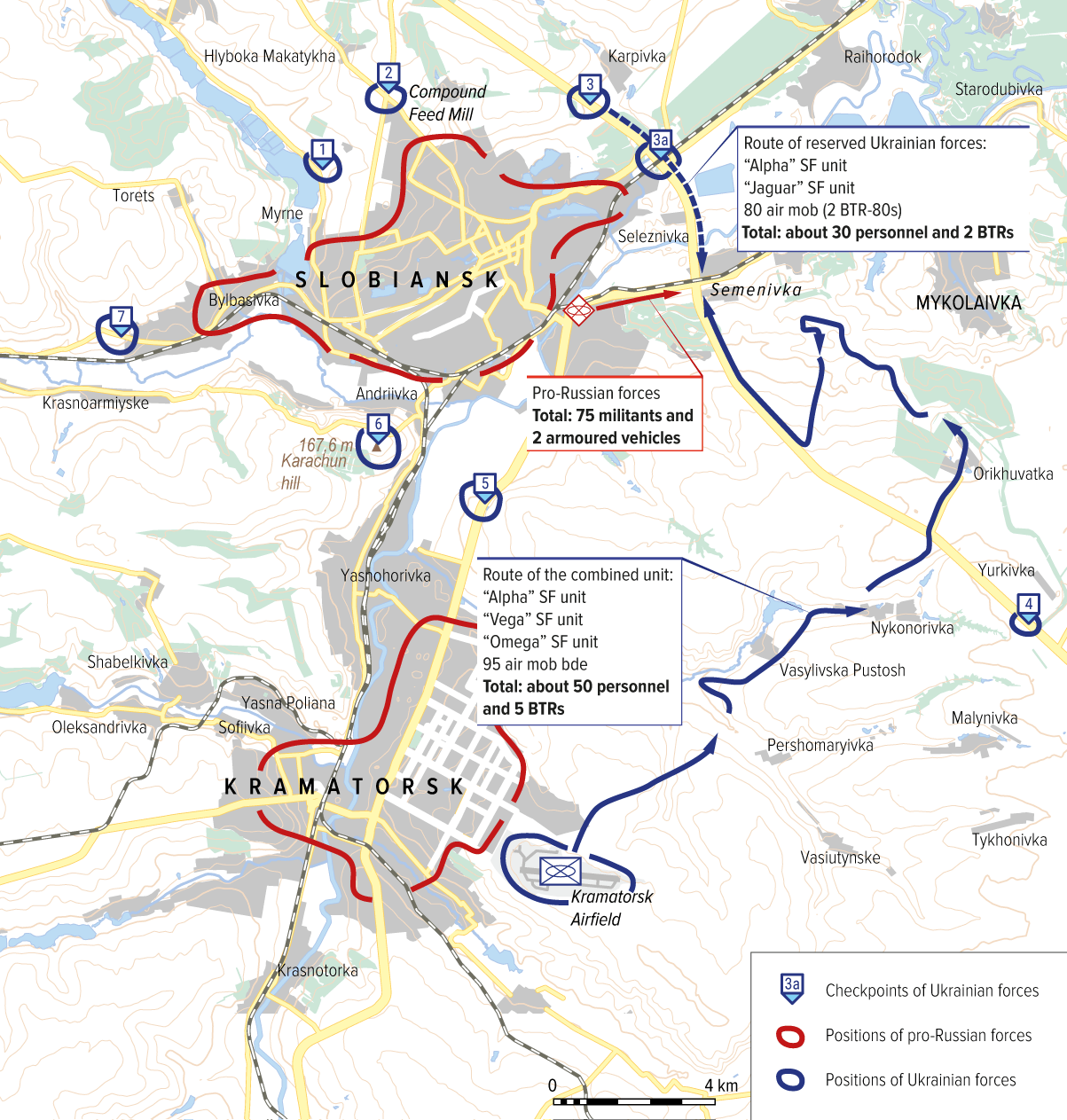

On May 5th, the Ukrainian command planned a force regrouping operation. By then, around 300 special operation fighters of the Interior Ministry (Omega, Vega, Jaguar) and 100 Alpha fighters from the SBU were in the entire Sloviansk—Kramatorsk area. Prior to that, a reinforcement group from the 95th separate airmobile brigade of the Armed Forces had come to Kramatorsk airport, so Ukrainian special forces of the various units of the National Guard and the SBU, which held the airport, could be used for more important tasks. The command intended to unite them in a single offensive force. For this purpose, the special forces had to be redeployed to a base outside Izium for further co-ordination.

Early in the morning, one small forward group was formed—SBU special forces received two armoured personnel carriers of the Jaguar regiment with 20 fighters as reinforcements. The group had to check the route to Izium for the passage of the main forces. Armoured personnel carriers were moving across the fields at high speed, and lightly-armed local collaborators at rare improvised checkpoints simply ran off when the column was approaching. This group bypassed Sloviansk and went towards Izyum unimpeded. Most likely, they were moving along the following route: Kramatorsk airport—Malynivka—Rai-Oleksandrivka—Krasnyi Lyman, thus bypassing Sloviansk in a wide arc. Having carried out reconnaissance, the group was called back to Sloviansk, to checkpoint No. 3-A, which was used as a command post; there were several senior officers of the National Guard and the SBU.

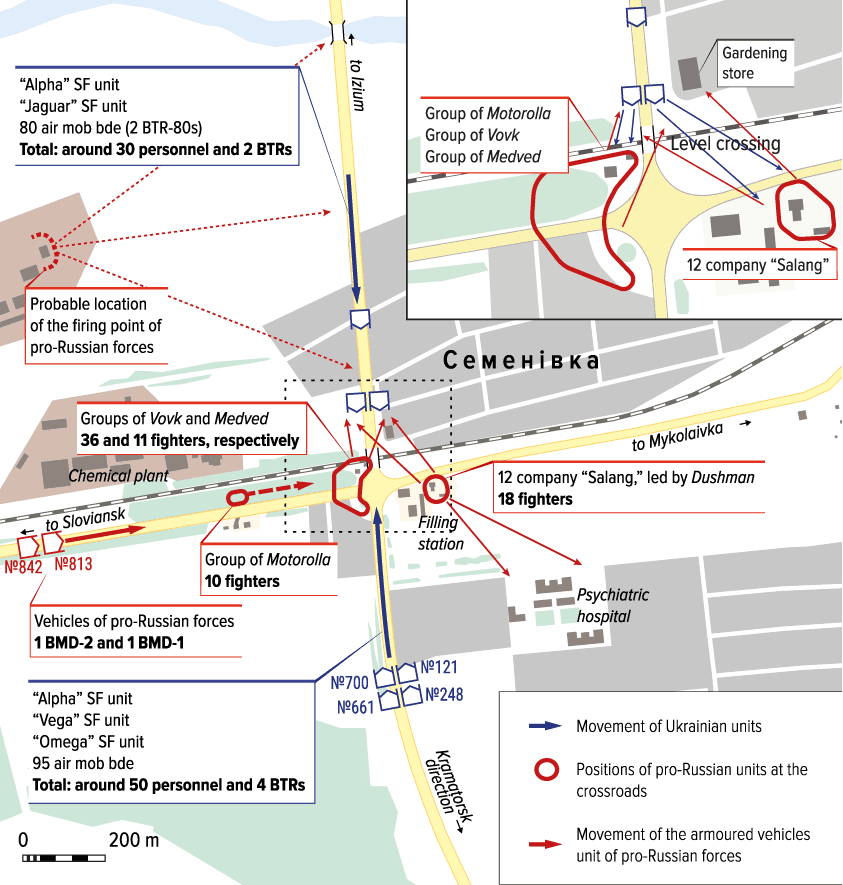

The command at the checkpoint explained to the group’s members that the main Ukrainian forces under the command of National Guard Colonel Serhii Asaveliuk had already left Kramatorsk airfield but went to Izium by another route, through Semenivka. The decision to lead the column of the main forces by that route was most likely taken by Major-General Yurii Allerov (call sign Karpaty (Carpathians)) of the National Guard. By then, the main column had already left Kramatorsk airfield and reached checkpoint No. 4. There, the scouts of the 8th special operations regiment of the Armed Forces of Ukraine assured that there was no one in Semenivka, and that the route was free. Allerov must have relied exactly on these data, and, therefore, the main column of the Ukrainian forces decided to take a much shorter route to Izium, along the main line of M03. Asaveliuk, however, took some security measures and wanted to bypass Semenivka by field roads, and only then return to Highway M03. However, when approaching the northern outskirts of Semenivka, the group detected the movement of militants. Asaveliuk decided not to engage them, and the column returned to the highway.

The actions of the militants warrant particular attention. That morning, the Salang group was commanded by Igor Girkin to take Mykolaivka. A group of 18 people set off in five cars, the models of which are known from the words of a militant—a Kia, a VAZ-2101, a VAZ-2103, a VAZ-2112, and a GAZelle. Some Russian sources put the size of the group at 36, but, most likely, they confuse it with the Volk (Wolf) group in the same battle. In addition, five cars would have hardly had room for 36 people. On its way to Mykolaivka, the group stopped at a fuelling station in Semenivka, near the crossroads and the railway crossing. Curiously enough, other militant groups had no coordination with the Salang group—moreover, the video of the battle and interviews make it appear as though other militants did not even suspect Salang’s presence at the Semenivka fuelling station.

And that morning, other groups of militants operated in Semenivka as well. On the morning of May 5th, according to Russian sources, Medved (Bear) group was tasked by Igor Girkin to go for “free hunting”—in other words, it was a mobile group. The group consisted of 17 people, and its commander, Vyacheslav Rudakov, call sign Medved (Bear), was born in Simferopol, served in an air assault battalion, and then was a Berkut figher. He took the command of the group only three days ago: It had been under the command of Romashka (Chamomile), killed on May 2nd. The group was divided into two parts—a forward squad of six people was under the command of an Afghan veteran, and the other 11 militants were with Medved. They moved to Semenivka. A militant from the Afghan squad spoke of those events:

“Our group came first to Semenivka. There we found two enemy APCs; they were moving to Semenivka from the airport, then they turned around at the crossroads and left. We tried to hit them with RPG-7, but the trigger malfunctioned. We were acting with no particular disguise, so we decided that we could be noticed. We went to another area, and the Medved group came to Semenivka after us.”

It seems that the militant described the meeting with Asaveiluk’s column. It is not certain which group of militants Asaveiluk’s column discovered when approaching Semenivka from the north—It could have been both the militants of the Salang group and the Afghan squad. In any case, after that meeting, both the Ukrainian and the pro-Russian parties knew about the presence of each other in the area of Semenivka.

The SBU officers from the forward group at checkpoint No. 3-A were ordered by the Alpha commander to move towards Asaveliuk’s column and check the route through Seleznivka and Semenivka. They were ordered to pay special attention to the railway crossing in Semenivka. It can be assumed that it was the discovery of the movement of militants in Semenivka that prompted reconnaissance of the area. Four SBU special operation officers got into an armoured minibus; at the checkpoint, they were provided with an armoured personnel carrier of the 80th airmobilebrigade under the command of Senior Lieutenant Vadym Sukharevskyi, call sign Borsuk (Badger). An SBU officer recalled that even civilians had warned them of militants:

“…On the other hand, many civilian vehicles stopped on seeing us, and the drivers said, ‘Guys, you are being waited for in Semenivka, there is an ambush and armed people there.’ Some said of 10 armed people, some said 20.”

At about 8:30am, the forward squad departed from checkpoint No. 3-A to Semenivka. On the outskirts of Semenivka, the squad stopped and, through optics, observed the situation—the railway crossing in Semenivka, the crossroads and the “greenery” nearby, and the industrial area to the right—but could not detect anything suspicious.

At that moment, Oleksandr Ustymenko, an SBU colonel who was in Asaveliuk’s column, which was moving to Semenivka from Kramatorsk, contacted an SBU officer from the forward squad, and said:

“Is that your minibus and APC? Are there four of you? We have intercepted radio communications—you are being watched by the enemy from close range.”

The Ukrainian forces had a minor tactical advantage: Right before, Omega special operation officers had captured the militants’ radio station, and therefore could eavesdrop their radio communications. The forward squad looked around, but could not detect the enemy observer. However, there could be no doubt: The officer spoke about them, and it was a confirmation that the militants knew about their presence. It is very likely that the observer was on one of the high-rise buildings in the industrial area near Semenivka. At 8:50am, the forward squad returned to checkpoint No. 3-A to report and clarify the task. At the checkpoint at that time, Major-General Allerov tasked the SBU officers to meet Asaveliuk’s column from Kramatorsk by marching towards Semenivka. The formulation of task, the formation of the column, and its departure lasted literally 10 minutes.

During the formation of the column at the checkpoint, a Ukrainian SBU officer recalls, the traffic of civilian vehicles on the highway was not blocked, and drivers could warn the militants about the movement of Ukrainian forces. Some cars would drive up, turn around and drive in the opposite direction—to the railroad crossing and the crossroads in Semenivka:

“In my opinion, the planning was hasty and absolutely not adequate to the situation. Car and people passed through the checkpoint, some of them went back, turning literally 50 metres away from the checkpoint and going back to the crossroads.”

In some way, a similar story about the actions of the militants was spread on Russian news resources, though some details look more like a Hollywood blockbuster, and seem to be entirely made up:

“… We went to another area, and the Medved band came to Semenivka after us. They passed the crossroads and turned towards Izium. At this very time, a composite squad of Ukrainian special forces, reinforced by four armoured vehicles with paratroopers, started moving towards them. When APCs appeared from the bridge, they were 100 to 120 metres away from out guys at most. Medved is a first class driver and always was behind the wheel, which saved the whole group then. The driver instantly made an escape turn, and two or three seconds later, the car, tightly packed with the militants and weapons, was already gaining momentum, moving away from the enemy. The first follow-up shots were in 20 to 25 seconds. Medved stopped the car at the crossroads and commanded, “Action!” And the protracted rifle battle began.”

Ukrainian soldiers and officers have no recollections of such a vivid meeting and shootout. However, the movement of Medved’s car in the direction of Izium, where checkpoint No. 3-A was located, and the story of an SBU officer have many similar moments. One can assume that, in fact, Medved behind the wheel of a civilian vehicle approached the checkpoint, saw a Ukrainian column preparing to move towards Semenivka, turned around and went to the crossroads to secure the position and warn the rest of the militants.

So, the Ukrainian column was formed and marched from checkpoint No. 3-A towards Semenivka at about 9:00am. It was led by an armoured minibus with SBU officers, followed by an armoured personnel carrier of the 80th brigade under Sukharevskyi’s command, and another two Jaguar APCs. The column began to move towards Semenivka and passed Seleznivka. It was moving at low speed, avoiding probable ambushes. In approaching the bridge in front of Semenivka, at about 9:10am, the first fire contact took place—the column was fired with small arms. The SBU officer spoke of those events:

“… We opened fire in response—in all directions, because we could not immediately discover firing points in the ‘greenery.’ The enemy was disguised. We were moving in the open area, and the enemy was firing. At that moment, it was necessary to make a decision: Whether to continue to go forward under fire, or to stop and circumvent the disguised positions from the flanks. But no one took such a decision, since the commanders remained on the base. Moreover, we continued moving on the road, although it would be logical not to get engaged, shooting at the ‘greenery,’ ‘industrial area’ and other dangerous directions at a distance. Such an order did not follow. We continued to seek our targets in the ‘greenery,’ when someone decided to go ahead under fire.”

Satellite images of the terrain reveal that it is difficult to detect large green areas, from which the militants could have fired at the armoured personnel carriers near the bridge across the river. However, the industrial zone, where a gas distribution station and a chemical plant are located, indeed has high buildings and facilities. The nearest of them is 800 metres away from the bridge. At this distance, it is quite possible to fire with a PK machine gun (effective firing range of 1000 metres) or a Dragunov sniper rifle (effective firing range of 1200 metres) at a target similar to a minibus or, moreover, armoured personnel carrier. Such weapons could hardly have caused any serious damage, but it would have been a matter of psychological pressure, with bullets periodically hitting armour. It is safe to assume that the militants were shooting from some high-rise building in the industrial area.

The Ukrainian column continued to move at low speed, and the Jaguar APCs came forward. At about 10:00am, they reached the railway crossing and stopped, the minibus and the APC of the 80th brigade also stopped 150 metres away. If the SBU officer recalls correctly, the column crossed the 950 metres between the bridge and the railway crossing for almost an hour. After stopping the first APCs at the crossing, the battle began at really short distances of literally several dozen metres to the militants’ positions. They concentrated their fire on those armoured personnel carriers. In turn, two armoured personnel carriers opened fire to the left and to the right.

The Salang group, which at that time was refuelling, opened fire at the Ukrainian vehicles. They fired Ukrainian APCs, and a building of a gardening shop located just on the line of fire. In particular, they carried out aimed fire at the first floor and the attic of the shop. At least two grenades from a rocket launcher hit the building. The Salanga militants fired in the opposite direction, too—in the area of the Sloviansk mental hospital, where they though a Ukrainian sniper was located.

The Ukrainian APCs at the crossing were being shot not only from the refuelling station to the left. The Volk group of 36 people secured positions near kiosks and the private sector, as well as near the railway booth and in the thick “greenery” near the railway. Thus, they attacked the Ukrainian forces from the right. They might have used a truck wagon, which stood near the large concrete slab “Sloviansk,” for cover. Although the wagon was burnt down in the battle, its shaft could provide protection.

The cross fire led to Ukrainian soldiers KIA and WIA. Jaguar warrant officer Victor Doliinskyi was with a grenade launcher in front, and when the launcher was hit, it detonated, and he died immediately. The SBU armoured minibus was sent forward to pick up the wounded while SBU officers of the SBU engaged in combat.

With a precise shot, the SBU sniper “took down” one of the militants at the refuelling station. Together with the SBU machine gunner, they opened focused fire at the refuelling station, and a gas container detonated. This explosion could be seen in three different videos—from RT correspondents, who were filming the scene from the neighbouring Ukrainian checkpoint, and from two local residents. Shaman, the commander of the Salang group, got 75% of his body burnt.

However, the Ukrainian fighters were still on the line of fire. The SBU sniper was injured by a rocket-propelled grenade that hit the APC:

“The enemy actively threw RPGs and VOGs at our immobile group. There was a strong explosion—most likely, an RPG grenade had exploded on the APC armour. Large splinters struck me in my right thigh and pierced the stomach. I was still conscious and tried to crawl away from the APC. But at that moment, infantry fire focused on me. Bullets started knocking around, and one of them went through my wrist and broke the bones. More than a dozen VOG splinters went through my left thigh.”

It can be assumed that this shot was made by a gunman called Hans from the Salang group. Three militants from this group (Lis (Fox), Dushman and Hans) moved from the refuelling station closer to the crossing. One of them described the battle as follows:

“… Hans shot at the first APC with a Mukha, hit it from the side, then came the infantry, we opened fire at the infantry. […] It was me, Dushman, and Hans, we fired at them with Mukhas, and then attacked them massively with Kalashnikov machine guns and assault rifles until the cartridges exhausted.”

The SBU sniper and the other wounded were loaded onto an armoured carrier, which began to retreat:

“In the APC in which I was evacuated, an RPG grenade hit the only box with sand on board, almost immediately after the start of the movement. It saved us—the explosion did not disrupt our car.”

Oleksandr Anishchenko, an SBU colonel, was probably killed at this moment. He helped evacuate the wounded, and died from the impact of a grenade when he was near the armoured carrier.

Ruslan Luzhevskyi, an SBU captain who had very solid fire training, took the position right in front of the enemy, lying under the curly concrete fence of the railway crossing. Later, he left the cover, but was injured and subsequently died.

The Ukrainian armoured personnel carriers began to retreat. The Ukrainian wounded and dead were still on the battlefield. At around that time, the Motorola squad of 10 people arrived (one of the cars was a silver Mitsubishi Outlander), joined the Volk and Medved groups, and continued to shoot at the Ukrainian armoured vehicles.

The battle was put to an end by Asaveliuk’s column. Having entered Semenivka via Highway M03 from the direction of Kramatorsk, they ended up in the enemy’s rear, making a surprising appearance. Militant Medved, who was lying with a machine gun behind a concrete pillar at the crossroads and firing at retreating APC, was eliminated by fire from the rear. The militants dispersed, Motorola drove on the bullet-ridden Outlander to Sloviansk. Asaveiluk’s column picked the wounded and the dead.

In Sloviansk, the militants were felling high poplars along the main roads to impede movement, fearing the onset of Ukrainian forces. The militants sent their armoured vehicles—BMD-1 and BMD-2—to the battlefield, but no one else was found there. It was about noon, and a short rain was about to begin.

Near the refuelling station, cars were burnt down—a VAZ-2103 and a second-generation Kia Rio hatchback. Those were two of the five vehicles belonging to the Salang group. The VAZ-2103 burnt about a hundred meters away from the refuelling station, and the Kia Rio hatchback practically at the station exit, which can be seen in the video right after the battle. It had probably caught fire in the blast.

Militant Lis from the Salang group said of at least 10 KIA and WIA in his group. He also claimed that several had been injured with 30mm ammunition or its splinters. He obviously exaggerated: Since 30mm ammunition tears a man’s limbs off, those wounds were probably caused by a 14.5mm machine gun of the APC, or from weapons of a smaller calibre. In addition, in this situation, only the militants had a 30mm cannon on the BMD-2. Friendly fire among the militants in the battle could really have been the case: The Volk group did not suspect that the Salang group was in the refuelling station area. Moreover, according to a militant from the Volk group, Motorola even ordered fire at the refuelling station area, arguing that Ukrainian forces were there. Five killed militants have been identified as of now. They included Vyacheslav Rudakov, call sign Medved, the commander of one of the squads, and Valery Parsegov, call sign Chechen, the deputy commander of the Salang group, killed by a sniper.

Having learnt about the battle at the railway crossing, Asaveliuk’s group got a bit separated—they had a defective APC and two unarmed trucks. This APC and trucks were sent by long bypass through Krasnyi Lyman—a route that the forward group had checked in the morning. The equipment reached Izium without any problems.

Two civilians died on that day. Iryna Boievets, a 30-year-old lecturer at a vocational school, was killed on her own balcony, probably with a stray bullet. 56-year-old Anatolii Kurochka died of injuries in his car—he was probably the driver of a wagon that burnt down at the crossroads.

On that day, a Mi-24 Ukrainian attack helicopter of the Armed Forces of Ukraine accomplished the task of destroying the militants’ improvised armoured train—they had put several coal wagons at a railroad crossing to Andriivka, thus blocking the road from Karachun to Sloviansk. The wheels of the wagons were welded to the rails, with loopholes cut through their walls. The helicopter destroyed this fortification. And at about 2:30pm on that day, Mi-24 29 “red” from the 11th army aviation brigade was shot down near Raihorodok. It is unclear whether this was the same helicopter that had destroyed the “armoured train” or not, but he was taken down with large-calibre machine guns that hit it on the left-hand side. The helicopter was still controllable, and the pilots were able to land it on water, into a flood land of Siverskyi Donets River to the north of Raihorodok. The crew consisted of two people, with no on-board technician, both of whom were rescued. The same day, a Su-25 attack aircraft struck the abandoned helicopter with missiles and completely destroyed it, so that pro-Russian forces could not take it even as a damaged trophy.

Semenivka remained under the control of the militants, and pro-Russian forces would soon secure their positions there. The village would often be in the spotlight as a place of fierce battles.

The Russian news media and all pro-Russian bloggers were not ashamed to spread the view that the Ukrainian army was deliberately firing unarmed civilians. On those days, the word “punisher” became part and parcel of the vocabulary of Russian propagandists. Russians had a “magnificent” picture of wounded and dead civilians, bullet-ridden civilian objects, burnt cars, and destroyed infrastructure. All this had a very powerful impact on the audience’s emotions. Of course, Ukrainian forces never pursued such “cannibalistic” intentions. But they were dragged into a very dirty game—battles in settlements. Such battles resulted in civilian casualties from the fire of both parties. Such casualties would be virtually inevitable as the conflict continued; therefore, the entire responsibility for them can only be placed on the aggressor, since the conflict began at its will.

Read also:

The contents of the article are licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. Copyright exceptions are marked with ©.

The article was prepared with the assistance of the Ministry of Information Policy of Ukraine.

Підтримати нас можна через:

Приват: 5169 3351 0164 7408 PayPal - [email protected] Стати нашим патроном за лінком ⬇

Subscribe to our newsletter

or on ours Telegram

Thank you!!

You are subscribed to our newsletter