Dmytro Putiata, Andrii Karbivnychyi, Vasyl Rudyka

On May 9th 2014, a group of pro-Russian militants led by the “Mongoose” tried to take control over a Mariupol city vital security site—the Police Headquarters. They planned to swiftly take over the building, simultaneously capturing a group of Ukrainian officers from several departments that were holding a meeting in said building. The pro-Russian militants took advantage of the assistance from several accomplices among the police and the increased workload of the rest of the police due to an ongoing holiday. Their plan failed, as the Ukrainian officers withstood an initial attack and held the 2nd floor of the building for several hours. The reinforcements of the National Guard of Ukraine, Armed Forces of Ukraine, and the “Azov” unit came to their aid and took the Police HQ by storm. As a result of that day’s events, according to official reports, 13 people were killed in the city: 2 policemen, 4 soldiers, 3 civilians, and 4 pro-Russian militants.

The events of May 9th 2014 in Mariupol were depicted in several documentaries by Ministry of Internal Affairs, Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), Hromadske TV of Pryazovia there were also published investigations by Euromaidan Mariupol community, Civic Solidarity (Memorial) observers, and analysis by Bellingcat in 2015. Nevertheless, this whole story still has a lot of blind spots and unanswered questions. Basically every witness’ story contains valuable evidence, but events in those stories are often mixed chronologically or have other contradictions. The timestamps from surveillance cameras, along with bystanders’ footage, granted us the ability to establish the accurate timing of some events up to a second. We’ll sum up facts and try to recreate a consistent story. We’ll also ask a number of questions that are crucial for further development of a comprehensive image of all the events of 9 May in Mariupol.

In early May 2014, the situation in Ukraine was threatening. The plan for the proclamation of puppet “people’s republics,” launched from Russia, which was based on Ukraine’s regions, and the intention to hold “referendums” was only a process of creating the appearance of legality—a cover for the further invasion of Russian troops. Russia was preparing the leverage to threaten the Ukrainian government or even grounds for justifying the occupation or annexation of a part of Ukraine. On April 12th, the Russian side moved from words to deeds: Sabotage and reconnaissance squads, led by Russian officers, seized a number of cities—Sloviansk, Kramatorsk, and Horlivka, while in others, the rebellion of local collaborators was being supported. Real fights continued around Sloviansk, with body count reaching dozens on both sides at the beginning of May.

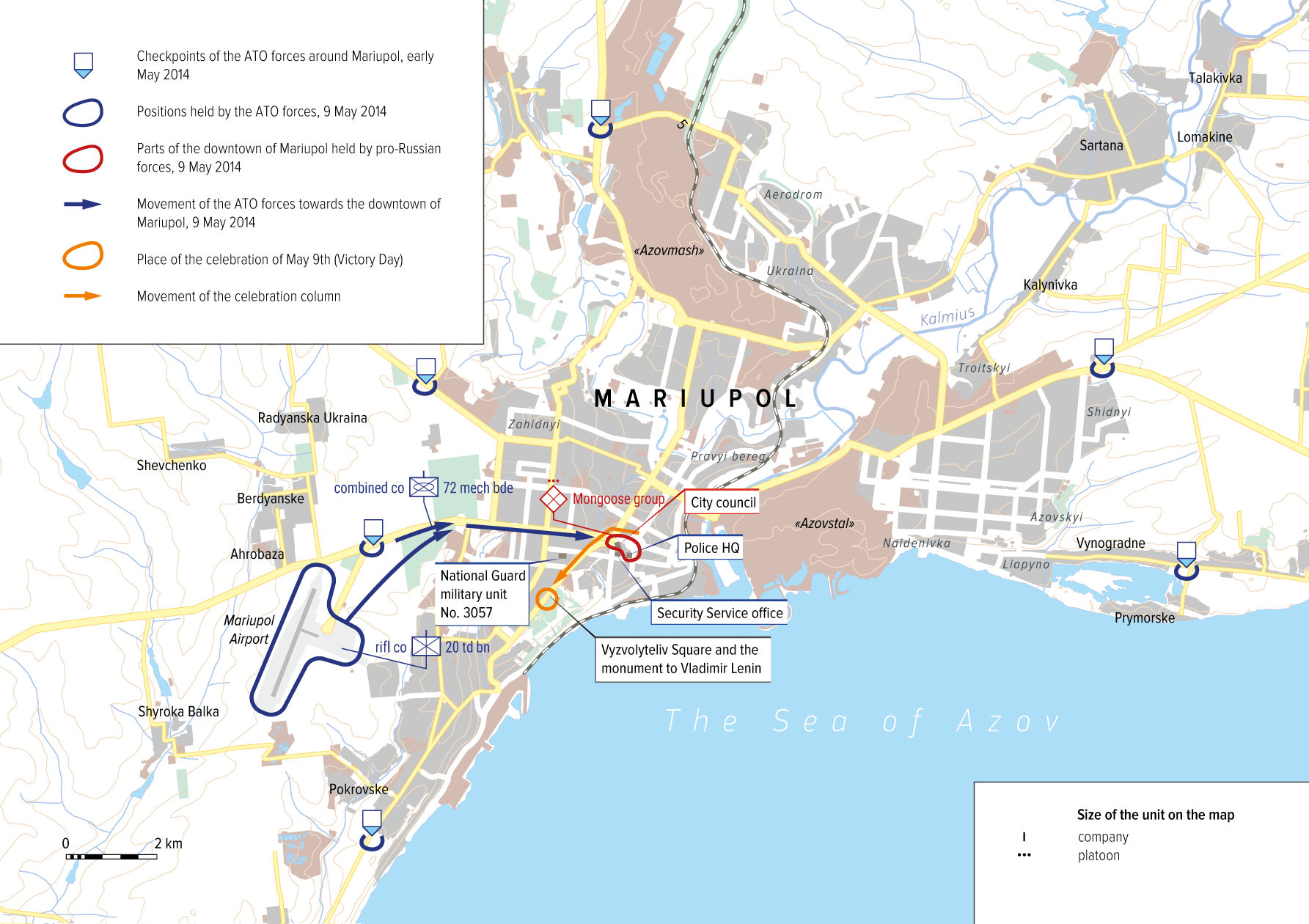

Under these conditions, the Ukrainian authorities took serious measures to localise the areas of action of Russian armed groups and not to allow them to exert influence on the surrounding cities. In particular, Sloviansk was being beleaguered in order to isolate Russian forces in it. Additional Ukrainian forces were deployed in Mariupol, too—units of the Armed Forces entered Mariupol airfield, checkpoints were set up around the city by the 72nd separate mechanised brigade with armoured vehicles. The units of the National Guard from Lutsk and Lviv reinforced the defence of National Guard military base No. 3057 in Mariupol, which was literally two or three blocks away from the historic centre of the city. On May 1st, the head of the Police in Mariupol was changed: Col. Valerii Andrushchuk was appointed for the post. The same day, pro-Russian activists under the banners of the “DNR” demanded the resignation of Andrushchuk; on the steps of the Police HQ building, he showed the protesters a written statement of his resignation, and the activists left. Andrushchuk remained in his post because such a statement was not legally valid—it had to be approved by the leadership of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. One of Andrushchuk’s decisions as head of the city Police was to summon a company of patrol service officers from Cherkasy (Central Ukraine) to Mariupol, since a significant part of the Mariupol patrol service officers were openly pro-Russian, cooperated with Russian agents in the city, and sabotaged orders.

In Mariupol itself, there already were several outbreaks of confrontation. On April 16th, almost simultaneously with the appearance of Russian sabotage groups in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, Russian collaborators attempted to capture military base No. 3057. An attempt to seize the unit failed—the troops opened fire first in the air, and then to kill. At least 19 attackers were injured, with 3 of them fatally. More successful for pro-Russian forces were attempts to seize the building of the Mariupol city council: They had been controlling it since March 18th, with a few interruptions. Ukrainian troops liberated the city council several times, but when the police departed, the building was seized again. Pro-Russian protesters were driven out of the building on the night of 6—7 May; and, by the newly arrived 20th territorial defence battalion of Dnipropetrovsk, on May 8th. However, in each case, pro-Russian forces returned the control over the building the very next day.

On 9 May 2014, the leadership of the Ukrainian security forces in the city organised a meeting. It was to begin around 9:30am, and consider the issues associated with the launch of the Anti-Terrorist Operations (ATO) in Mariupol.

The meeting was attended by head of the city Police Valerii Andrushchuk at the Police Headquarters; Col Andrii Diermin of the Operational Command South; deputy commander of the 20th territorial defence battalion Lt Col Serhii Demidenko; commander of National Guard military base No. 3057 Col Serhii Sovinskyi; one of the head of the anti-terrorist operation in Mariupol, Oleksandr Nabokov; Head of the Traffic Police Col Victor Saienko; police Col Mykola Poboinyi; and several others—Andrushchuk’s deputies, and a representative of the Cherkasy patrol police. At 9:00am, Andrushchuk just returned from the ceremony of the solemn greeting of Second World War veterans and laying flowers, which took place at 8:00am on Leninskyi Komsomol Square (now named Square of Soldiers-Liberators). Andrushchuk had been invited by the mayor of Mariupol, Yurii Khotlubei. Residents of Mariupol, who were celebrating May 9th, would soon go to the square through Lenin Avenue (now named Myru Avenue) and Nakhimova Avenue: They had met in the downtown near the Mariupol drama theatre, and then moved in a large column at around 10am.

The meeting did not begin until 10:00am, since local MPs Chekmak, Ivanov and Klymenko came to the Police HQ to negotiate with Andrushchuk. They were openly pro-Russian and, according to Andrushchuk, he tried to resolve the issue of espionage by taxi drivers for militants. The negotiations yielded nothing, and the deputies left the building.

At around 10:05am—10:10 am, ten minutes after the meeting started, an operational officer in the police department reported that the building was surrounded by people in masks, and that attempts were made to seize it.

“The terrorists perfectly timed the assault: In the city police department, there was only the guard duty, maintenance staff, and representatives of the law enforcement agencies that had arrived at the meeting. All police officers were maintaining public order in different parts of the city. Also, the attackers were clever to take advantage of the situation when the civilian population was on the city squares in large numbers, and provocateurs could easily engage people in mass disturbances,” says Oleksandr Nabok.

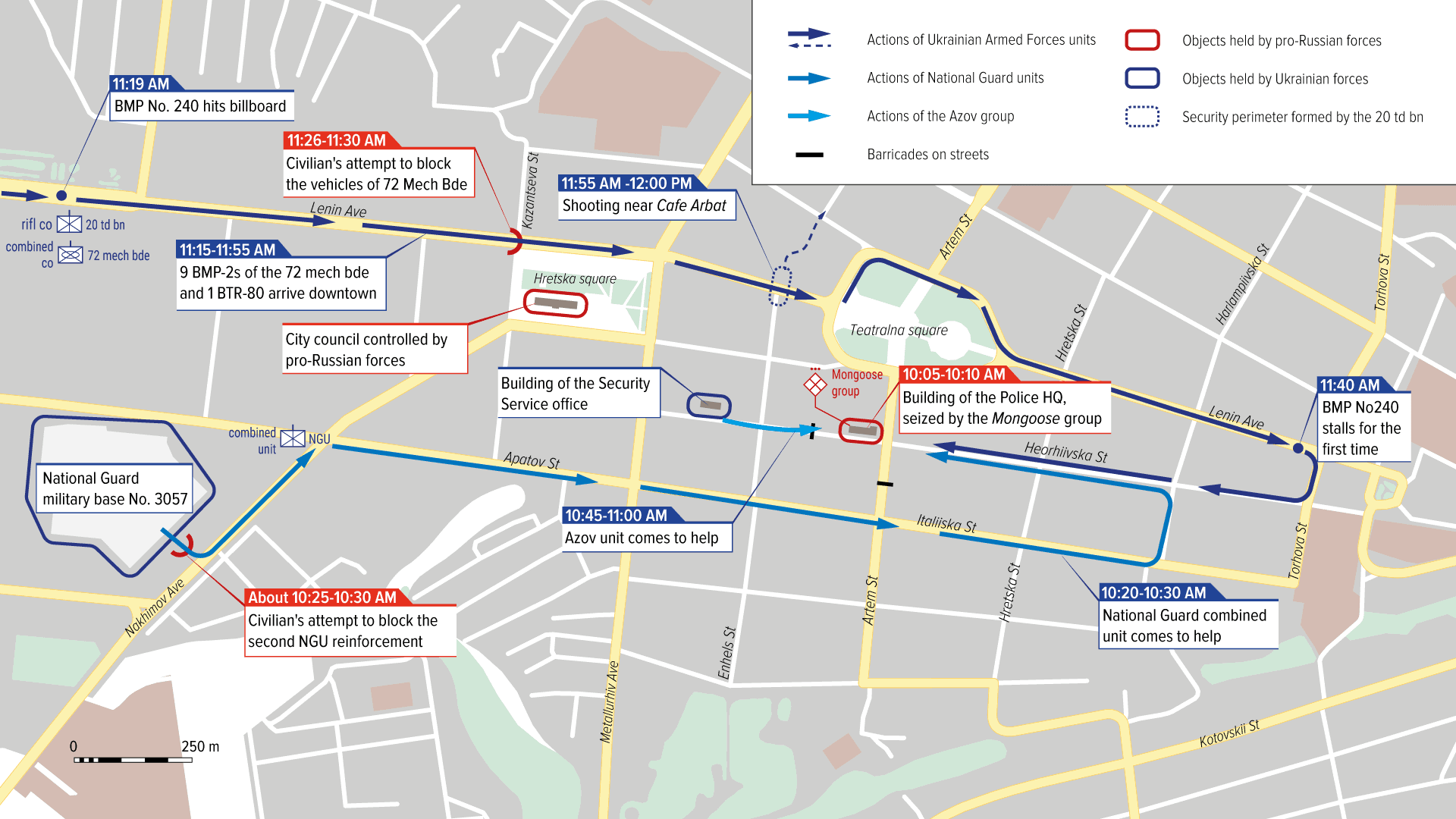

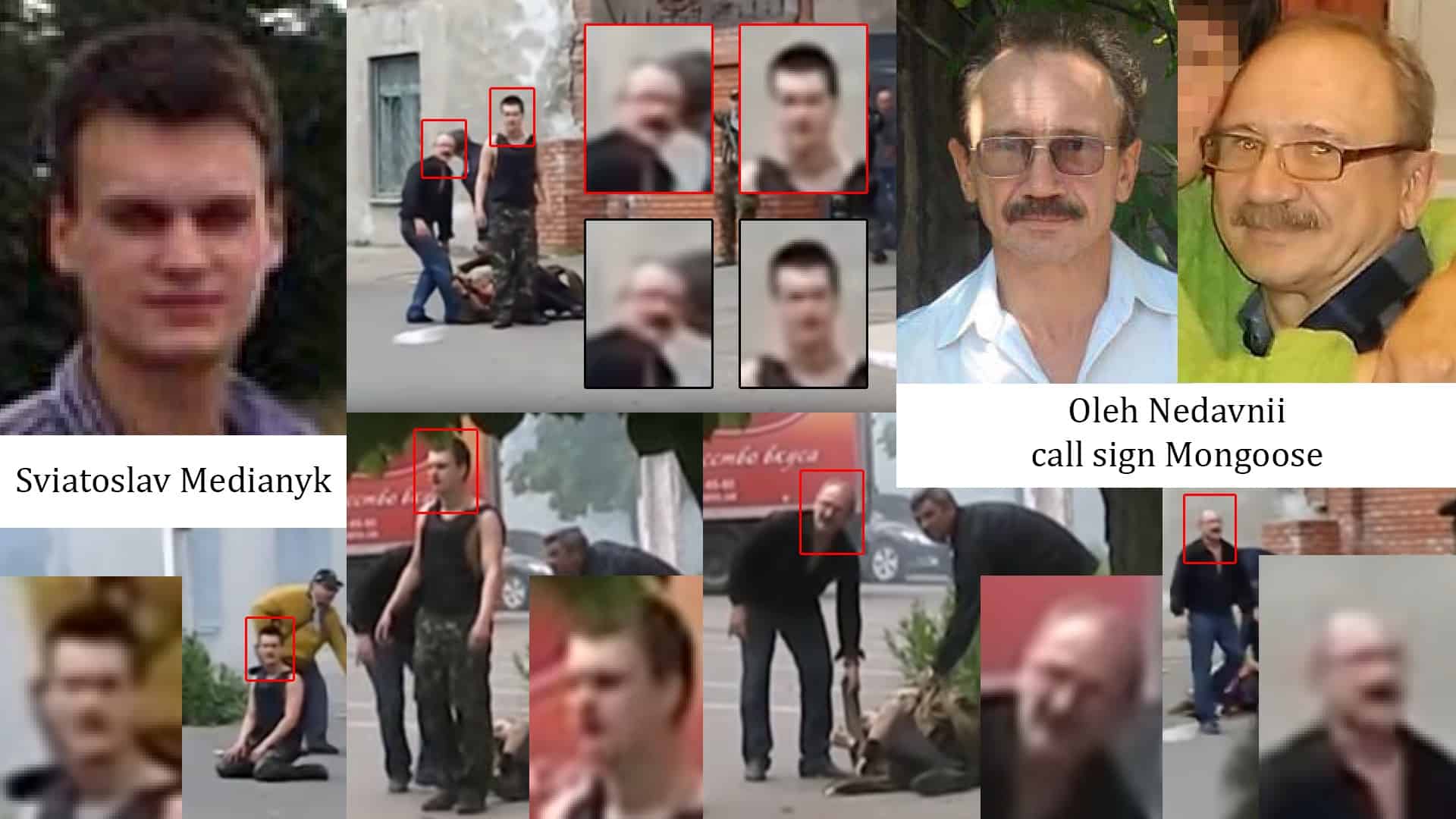

In total, there were 25 militants excluding snipers, who were divided into two groups, each having different roles. The assault team was commanded by Oleh Nedavnii, a native resident of Mariupol (call sign Mongoose aka Anatolich), and consisted of approximately 10 people in camouflage, mostly of sandy colour, who were supposed to immediately seize the building. The second group (the “cover group”) was supposed to block traffic in the streets adjacent to the Police HQ. It had 15 people in civilian clothes, with some wearing a balaclava or a medical mask; the whole group had several assault rifles and pistols. They were blocking traffic in the streets by putting garbage bins across Artema Street; Heorhiivska Street was blocked by a truck of Luciano sweets. According to the militants, Oleh Nedavnii had also arranged that concrete blocks and sand would be brought to the Police HQ, but people with whom we had arranged so seemed to have changed their minds—the building materials were never brought, and no serious barricades were created under the building.

It was not easy to get into the Police HQ: The main door was hard-armoured, with a small window made of bullet-proof glass; even the handle had been removed from the outside of the door after the May 1st events. It was possible to get into the building only if it was opened from the inside. According to Andrushchuk and the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), in order to get inside, the assault group of militants resorted to tricks: Three armed men in camouflage were leading one of his accomplices in civilian clothes, holding his hands, and allegedly produced fake documents. Police officer opened the door, and the gunmen stormed inside and opened fire on the walls and ceiling, demoralising the few policemen who were there. How the militants managed to convince the guard officer that they were law enforcement officers, and why they were let in, is still unknown. The militants got inside, and those few present policemen were disarmed and gathered at the public office. The militants quickly took the ground and first floor of the building, but were met with resistance on the second floor. Andrushchuk’s office was located there on the second floor, and after the first shots in the building, meeting’s two participants—Demidenko with a Kalashnikov assault rifle, and Poboinyi with a Makarov pistol—ran into the corridor and prevented the militants from reaching the second floor.

In the first 10—15 minutes of the assault, Traffic Police Chief Col. Viktor Saienko and warrant officer Mykhailo Yermolenko died of fatal shots. The circumstances of their death, stated by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the SBU, raise more questions than they answer, and will be considered separately.

Attempts by the militants to quickly seize the Police HQ failed due to the resistance of several officers who attended the meeting—Demydenko, Poboinyi, and Col. Andrii Diermin, who joined them later. They barricaded one of the two flights of stairs, which led to the second floor of the building, found one Kalashnikov assault rifle a room on the second floor, and kept a bead on the corridor and two flights of stairs. Serhii Demydenko was injured during these shootings—the bullet hit him in the leg, and he bled in a matter of minutes.

While the three officers were resisting, the other members of the meeting in Andrushchuk’s office were able to call for help by calling National Guard military base No. 3057, units of the 72nd mechanised brigade, which were guarding at the checkpoints around the city, the 20th territorial defence battalion, and a group of the Azov battalion, which had arrived in the city shortly before.

However, the militants managed to strengthen the external group using the arms taken in the building, including a machine gun. The militant Serhii Hrytsenko, call sign Tiulen (Seal), later said during the interrogation,

“…When N. gave me an assault rifle [AKSU] near the Police HQ, he also gave someone a Makarov pistol, but I did not notice who that person was. He also said that they had not opened the weapon storage room yet, but when they do, there will be a great many of weapons. Then, N. hid inside the building. We did not have bulletproof vests. The shooting in the building was petering out.”

In order to help the police officers detained in the Police HQ, the first composite squad of the National Guard moved from military base No. 3057. At around 10:20am, 15 minutes after the “Mongoose” group began the assault, the NGU squad arrived in the area. The National Guard officers left their vehicles one block away from the Police HQ, on the corner of Hretska St and Heorhiivska St. The squad headed for the building on foot.

When the National Guard officers appeared, Mykola Piatin, a member of the “cover group” of the militants, stopped a trolleybus which was driving towards the railway station, thus blocking Heorhiivska St.

When approaching, the guards were fired by the militants, who were holding the Police HQ and its perimeter. The National Guard squad was forced to withdraw, suffering losses. One serviceman—Bohdan Shlemkevych, a senior soldier of the 45th Lviv regiment of the National Guard,—was killed; several other fighters were wounded.

“As soon as we went out to Heorhiivska Street, we were met with dense fire with automatic weapons and a machine gun. It was then that our military unit suffered losses. Major Dmytro Afanasiev and soldier Roman Sapila were wounded; senior soldier Bohdan Shlemkevych was killed. Lt Col Stepan Lohush, the commander of the Lutsk division of the National Guard, was also wounded,” said Col Valerii Smolov, the commander of the Lviv regiment of the National Guard.

Automatic firearms shooting was heard in the city at 10:20am, and long bursts of a machine gun fire were heard at 10:22am. The sounds of gunfire were reflected in social media messages.

The militants also suffered losses in the shootout, with at least two wounded. Serhii Hrytsenko aka Tiulen described this first fire contact during his interrogation:

“…People in camouflage were approaching from the direction of Azovstal, along Heorhiivska Street. I do not remember who started shooting. I hid behind a tree. When a shot hit the tree, I tried firing back, but the assault rifle would not work. The situation was beyond control. N. left the building and said that, given the circumstances, we would be entering the Police HQ. […] The building was first entered by the wounded—N1., with a wounded buttock and a cheek raked with fire, and N2., with a through-and-through wound in the wrist.”

After the shootout, some members of the “cover group” of the militants came inside the Police HQ, while others fled from the area. Thus, there were 15 to 20 militants left in the building.

During this period of calm, at around 10:45am—11:00am, the militants released the hostages into the yard—the staff of the Police HQ, who soon ran away through the fence. The trolleybus was also removed from Heorhiivska Street, not to be seen later.

The commanders of the militants used this period of calm to mobilise the civilian population as well. From the seized building, they telephoned their network of provocateurs in the city. The holiday column had just (at 10:25am—10:30am) come to Leninskyi Komsomol Square and began a rally on the occasion of Victory Day (May 9th). The provocateurs at this rally announced the main myth of the day that spread around the city like fire: “Ukrainian punishers are destroying the police, who have sided with the people, refusing to shoot the festive parade.”

It was at this time (around 10:45am—11:00am) that the Azov officers were heading for the Police HQ. They had been summoned by Oleksandr Nabok, who participated in the meeting at Andrushchuk’s office. The Azov squad was very small, with only 10 people and an SBU officer who accompanied them. Azov fighters were garrisoned not that far, a block away from the Police HQ, in the building of the SBU (77 Heorhiivska St). For a number of reasons, the Azov fighters did not have a single uniform: Some four men had a black uniform, one or two in different camouflage, and the rest were in civilian clothes. For the entire squad, there were one or two bulletproof vests and a metal helmet. There were at least three reasons therefor: First, the Azov battalion was just being created; second, the unit had arrived in Mariupol shortly before; third, the call was sudden.

Yaroslav Honchar, the commander of the squad and then deputy commander of the Azov battalion, repeatedly stated in his interviews that when they approached the Police HQ, they did not immediately understand why they had been called—the building was not visibly damaged; its windows and doors were closed; the surrounding area was quiet and deserted. One of the Azov fighters get over the fence of the backyard of the building, he opened the door from the inside, and the group went to the courtyard. In several interviews, Honchar and the SBU claimed that Azov then managed to seize the ground floor of the Police HQ building, thus pushing the militants to the first floor. In this battle, the unit lost one soldier, Rodion Dobrodomov.

However, there are many circumstances that question this account of the events. In more or less detail, the circumstances of the death of Dobrodomov are available in the interview with Honchar—his press conference at the Ukrainian Crisis Media Centre on 12 May 2014, three days after those events. There, he gave the details of the death of Rodion: He was moving through the courtyard of the Police HQ, clearing up his sector. A militant was hiding between the parked cars in the yard, and when Rodion approached him, the militant, realising that he would be noticed in a moment, opened fire. When the Azov fighters came to the wounded Dobrodomov, the doctor confirmed his death.

“Each serviceman covers his sector. He [Rodion Dobrodomov] was covering his own, being within the sight of another soldier. However, it turned out that a terrorist was hiding in the courtyard between parked cars. In principle, had he been somewhat courageous, he could have killed us all in the back, since we had walked through the courtyard. But, apparently, he was scared and sitting between the cars. When Rodion started entering his sector, he realised that he would be noticed in a moment, and he had no choice but to shoot,” said Yaroslav Honchar.

Thus, Azov, after entering the backyard of the Police HQ, lost Rodion Dobrodomov in a shootout, did not dare to storm the building and, for some time, simply kept the position, expecting changes in the situation.

At around 10:25—10:30am, right after the celebration column had passed the gates of the military base, a second National Guard reinforcement was sent from military base No. 3057. The reinforcement was insignificant—a Bohdan bus (white-coloured, with tinted glass) with some 30 soldiers, all of them young conscripts. When the bus tried to leave the military base and enter Nakhimov Avenue, there was a minor incident—several civilians tried to block the exit with car tyres. Apparently, rumours of the “police that has sided with the people” had already spread, and some residents thus tried to stop the “Ukrainian punishers” from going towards the Police HQ. Several National Guard servicemen first fired some warning shots in the air, and then in the ground. The tyres from the road were removed, and the Bohdan bus continued its way. However, the incident did happen—some shots in the asphalt ricocheted and wounded one man. The injury was not fatal, and people nearby helped the wounded man. It should be noted that this scenario—”shots in the air, in the asphalt, ricochet, wounds”—would be repeated in Mariupol that day in virtually every clash with the civilians, in many places, and leave at least a dozen wounded.

At around 11:10am—11:15am, the armoured vehicles of the 72nd separate mechanised brigade of the Armed Forces of Ukraine entered the city. It was arranged in two separate columns, by one route, but at a 25—30-minute interval. In total, nine BMP-2s and one BTR-80 armoured personnel carrier entered the city.

The first column consisted of four BMPs with numbers 240, 241 (under the flag), 242 (under the flag), and 205. The column was accompanied by a dark VW Passat of the Traffic Police. The first column was involved in several incidents while entering the city, which will be discussed further.

The second column consisted of five BMPs with numbers 200 (under the flag), 203, 204, 372, and 254, as well as a BTR-80 with number 612. The column was accompanied by a white Toyota Prius.

Looking ahead, it should be noted that video from surveillance cameras at the road intersections revealed that in total, the armoured vehicles were in the downtown for 2 hours, 1 minute and 35 seconds. This is how much time it took from the moment when the first BMP arrived at the downtown at 11:25:05am, and the last one came out at 1:26:40pm after all the events of that day.

At 11:19am, an incident took place in the first column of BMPs. While moving along Lenin Avenue, BMP No. 240 crashed at full speed into the pillar of the billboard, which stood on the dividing line of the avenue, and flipped over into oncoming traffic. The BMP ran down both the billboard and a tree behind it. Rumour had it that the BMP driver had run down the billboard on purpose, having allegedly seen some kind of DNR-ish propaganda or a call for a secession referendum. This is not true: The dash-cam footage shows that the billboard was completely empty on both sides. The most likely cause of the incident was a malfunction of the BMP—it is clear that the vehicle was emitting a lot of fumes right before the crash, which had not been the case when it had been entering the city. It is worth mentioning that both dash cams had incorrect time settings (one hour early compared to Kyiv time) due to neglected Daylight saving time (DST). Other footage from that day shows that the entire right side of the combat vehicle No. 240 was covered with soot.

Armored vehicles that were moving behind BMP No. 240 followed it, crossed the dividing line and drove into the oncoming traffic lane. They may have followed the commander. After that, the crews of three BMPs apparently realised that there was a technical malfunction and were commanded to return onto the previous route. To do this, they turned around and went backwards in search of a place to turn over according to the traffic rules, where, after making a few loops, they continued to move to the Police HQ, but not in a column, but in separate groups, and in somewhat changed order: 240, 241 205, 242.

At 11:24:41am, the first BMP in the column entered the intersection from Kazantseva Street and passed past the square in front of the city council, which at that time was being held by pro-Russian forces. This is where another incident occurred with the column. A full amateur video of the incident helped establish its exact details and timeline.

At 11:25am, a traffic police car, BMP No. 240 and BMP No. 241 successfully passed the area. There were problems with BMP No. 205, which came a minute later. On entering the intersection with Kazantseva Street, it was stopped—first by a few people, and then the crowd. Paving blocks and car tyres were thrown at the BMP; a bald man in a bright jacket tried to throw garbage into the exhaust pipe; and a young man climbed the BMP tower and closed its optics (triplets used for observation) with tarpaulin. Despite such resistance, the BMP driver demonstrated utmost professionalism—it took him just over two minutes to cautiously worm the way through the crowd and gain speed while not injuring anyone. The bald man ran after the BMP for some time, trying to throw a tyre on it. From under the trees on the pavement, a man in dark sportswear threw a triangular pavement stone, which hit the top of the BMP turret, bounced off and hit the bald man’s head, stripping off skin on his skull.

Attempts were also made to stop BMP No. 242 in the column, but it was delayed for only 20 seconds. Already gaining speed, it skillfully circumvented a provocateur standing in the middle of the road.

These four BMPs crossed the intersection of Lenin Avenue and Metallurhiv Avenue at 11:25:05am—11:31:35am. Next, the armoured vehicles went around the park in the city centre and the Drama Theatre on the external circle (against the one-way traffic), and went to the Police HQ, having made a large detour through Torhova Street.

Half an hour later, at 11:55am, the intersection of Lenin Avenue and Kazantseva Street near the city council was passed by the second column of armoured vehicles (BMPs Nos. 200, 203, 204, 372, and 254, and BTR-80 No. 612), without any resistance from pro-Russian activists. It should be noted that tyres had already been burnt near the city council, with a black thick column of smoke hanging above.

The incidents with the first column, meanwhile, did not end: BMP No. 240, which had crashed into the billboard that morning, stalled at the corner of Lenin Avenue and Torhova Street. The armoured vehicle was surrounded by locals, who provoked the soldiers, but they exhibited extreme professionalism, decency and cold-bloodedness. The BMP stood for at least half an hour before it was towed away by BMP No. 204, which came in the second column.

The appearance of armoured vehicles in the city and rumours of the “shooting up of rebel policemen” seriously disturbed the residents. The intersection at the corner of Lenin Avenue and Engels Street at 11:30am was being kept by Ukrainian servicemen—soldiers of the 20th territorial defence battalion. With their presence alone, they caused the indignation of the crowd that began to come to the intersection. Some people from the crowd came directly to the military and provoked them.

The situation deteriorated rapidly at 11:55am, when the second column of armoured vehicles appeared on the avenue. One man rushed to the armoured vehicle, and the soldiers at the intersection fired warning shots into the ground, one of which ricocheted and injured the man. His behaviour in the street before the injury showed that he was intoxicated. Alcoholic intoxication was confirmed in the report by Civic Solidarity (Memorial) observers, who also noted that he could have been run over but for the warning shots. On the whole, five people were non-lethally injured due to ricocheted bullets, which bounced off the asphalt and the pavement.

Separately, it is necessary to dwell on the events that led to the death of Oleh Koloshynskyi, a resident of Mariupol, during the shootout. A minute before his death, another Mariupol resident in a blue jacket pulled out a pistol and at 11:59:01am shot twice at the Ukrainian soldiers. He was identified as an Anti-Maidan protester, a member of Solidarnist organisation, and Valerii Onatskyi’s associate. He shot with a 9×29 mm revolver. He made another two shots at 11:59:25am and immediately hid behind the crowd. After a one-second-and-a-half pause, a Ukrainian soldier made five rapid shots with an AKM in response, and Oleh Koloshynskyi fell on the ground, shot in the head and the leg.

This incident was thoroughly investigated by the author of the @UkraineAtWar blog, who processed video footage from the scene and found the moment when the fatal injury was inflicted. Koloshynskyi had been right between the Ukrainian soldier and the anti-Maidan shooter. The slow-motion video reproduced the moment of the injury—one of the first three AKM shots hit Koloshynskyi in the leg, he reflexively leaned, grabbing his wound on his leg, and then was shot in the head. That is, the bullet which hit Koloshynskyi’s head was aimed at about the level of his belt.

The analysis of this incident leads to two conclusions: First, the Ukrainian soldier did not intend to shoot to kill—he was shooting at the level of the feet, trying only to wound the shooter; and second, the attempt to fire in such a dense crowd could not have failed to lead to civilian casualties.

At approximately 12:10am—12:25am, Ukrainian BMPs finally arrived at the Police HQ. Two of them—No. 242 and No. 241—were located directly under the windows of the building in Heorhiivska Street; another three (Nos. 205, 203, 200) were at the intersection and down Artem Street (Nos. 205, 203, 200); four (Nos. 372, 254, and No. 204, which towed the malfunctioning No. 240) were lined up in a column along Heorhiivska Street; and the APC stopped even further—at the corner of Heorhiivska Street and Hretska Street.

The armoured vehicles were commanded to open fire—the firing with 30mm guns lasted for about five minutes. They targeted the ground and first floor of the building, mostly its side from Artema Street, which had received serious damage. But the front of the building was mostly left unaffected because it was hit with 30mm shells only up to 10 times. The brick walls were unable to offer protection from 30mm guns and were pierced. Meanwhile, the militants barricaded on the first floor in the office with windows into the yard of the building, that is, they occupied the most distant position in the building in order to protect themselves from the fire of the armoured vehicles.

The shelling of the combat vehicles was rather devastating, but the building did not catch fire at the time. Something was burning near the central entrance; perhaps there were other small local ignitions inside the building, but a big fire would not take place for another hour.

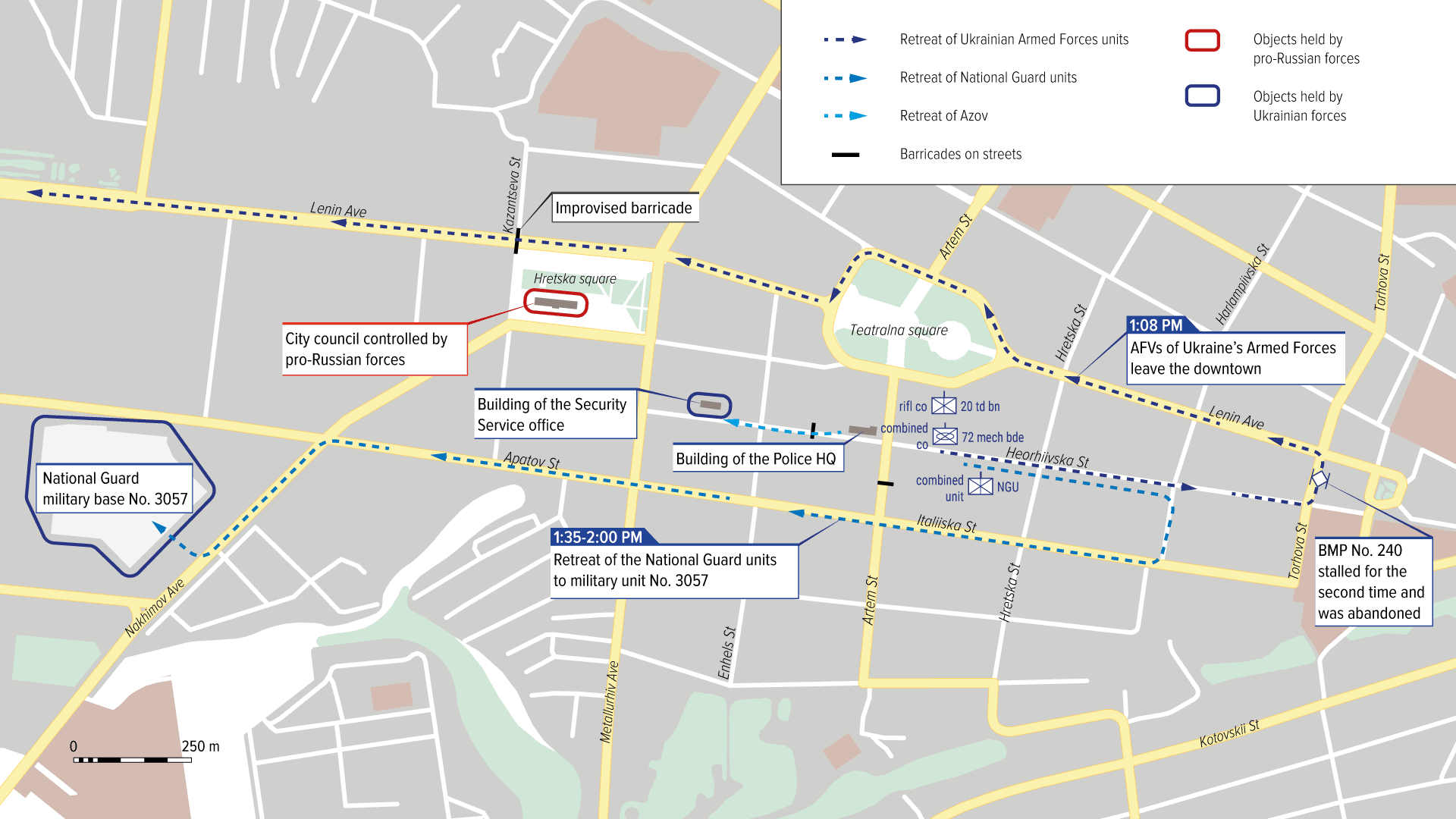

After the attack finished, the Azov assault group entered the Police HQ through the rear entrance. They walked through the building without encountering resistance, and opened the central armoured front door from the inside.

At 12:42pm, the Azov fighters appeared on the doorstep of the central entrance of the Police HQ and were arrested—the National Guard servicemen did not know the password they said due to poor coordination between different security structures. Therefore, the National Guard and Armed Forces soldiers arrested, disarmed and handcuffed four people—three Azov fighters (Yaroslav Honchar and two others) and an officer, head of the SBU of Mariupol. Later, Yaroslav Honchar said that it was them who were mistakenly named “four detained militants” in Arsen Avakov’s (Minister of Internal Affairs of Ukraine) report. People from the crowd, on the contrary, mistakenly believed that they were the “captured rebel policemen,” and tried to take them from the National Guard soldiers.

The Ukrainian servicemen then believed that they had completely suppressed the resistance of the militants. The officer calmly lined the soldiers before the armoured vehicles, right in front of the damaged Police HQ, without thinking that they would be fired at. All that time, indignant civilians, with a crowd of 100 to 150 people, stood near the building. The combat vehicles began to leave the building in the same way that they had come up to it. They did their job and were not going to get into the crowd again.

At 12:58:30pm, a single shot was heard. Oleksandr Kondrashyn, an Azov fighter, who stood near the entrance to the courtyard of the Police HQ, fell. In a moment, the National Guard and Armed Forces soldiers, who were freely standing in the street, fled under the protection of trees, took positions behind the parked cars and opened dense yet random fire with assault rifles at the first and second floor of the Police HQ. Kondrashyn was dragged to the inner courtyard of the Police HQ, and a tourniquet was immediately applied to his wounded right leg, near the ankle. Yaroslav Honchar recalled that the tourniquet had been applied at 1:00pm sharp.

At the same time, approximately at 1:00pm, a white Bohdan bus arrived, with completely curtained windows, and drove into the courtyard of the Police HQ. Most likely, the Omega special operations assault group arrived in the bus. Several minutes later, fire trucks came to the building.

Meanwhile, the crowd aggressively broke out the bars on the ground floor windows, trying to help people inside get out. The civilians climbed into the building, searched the premises, returned through the broken windows to the street—there was a mess. They could not find anyone—both firefighters and volunteers from the citizens who came to the ground floor did not find either people or bodies.

Taking advantage of the general mess, as well as the moral support of hundreds of civilians near the building, all the militants who had taken part in the assault on the Police HQ and were still alive, managed to somehow escape from the battlefield that day. Some of them through the windows, while others were released by Ukrainian law enforcement officers.

At 1:06pm, an incident involving the shooting of an ambulance car took place. From the second floor of the Police HQ, a man was brought down by a fire ladder, and civilians near the building put him in an ambulance car. After that, one of the Ukrainian soldiers (an Azov fighter, or a soldier of the 20th territorial defence battalion) opened fire at the car. The civilians believed that the ambulance car had taken people from the pro-Russian side, “rebel policemen.” Despite the fire in its direction, the ambulance car did not stop and departed from the Police HQ, but soon stopped at the roundabout near the central city park, with the flat rear tyre. The driver claimed that three people had been put into the car, and all three had immediately left it after it had stopped. The identity of those people is unknown. In two documentary films, police Col. Mykola Poboinyi and an SBU officer claim that an Ukrainian officer who had previously been at the meeting, had been put into that ambulance car. However, it is difficult to establish whether the man indeed belonged in the Ukrainian army. The Ukrainian soldier who had shot at the car had apparently thought him to be an enemy and tried to prevent his escape. The attempt was unsuccessful, and the shooting of the ambulance car angered the civilians.

At 1:08pm, the last three BMPs (Nos. 200, 241, and 242) drove away from the building, all under Ukrainian flags.

At 1:12pm, an incident happened that foreboded a major fire in the Police HQ. By that time, the fire was not big—the central entrance was hardly burning, something inside the building was smouldering, with smoke seen in the yard. But at 1:12pm, light-grey smoke started rising actively from a first floor window. The smoke poured out literally for 15 seconds, then stopped. And just five minutes later, at 1:17pm, a really strong column of black smoke started rising from the second floor. It took another 30 to 40 minutes for the entire building to be ablaze.

At 1:18pm, four people appeared from the Police HQ yard carrying the body of Mykhailo Yermolenko. Two of them were the militants who were inside the building—Oleh Nedavnii, call sign Mongoose, the commander of a group of militants, and Sviatoslav Medianyk, wearing a bulletproof vest next to the skin. The identity of another man is not established, and the fourth was a Ukrainian special operation soldier in a heavy bulletproof vest and a helmet. The special operations soldier returned to the yard, while the two militants and two other civilians further carried the body of Yermolenko, under the watchful eye of a gunman in a yellow jacket. However, Nedavnii and Medianyk weren’t detained and disappeared later that day—the supervision of a gunman was apparently ineffective.

At 1:22pm, Azov fighters carried their wounded soldier, Oleksandr Kondrashyn, on the improvised stretchers—a door taken off the hinges—from the yard of the Police HQ. A tourniquet was applied to his right leg, wounded near the ankle.

After 1:30pm, the crowd managed to force the Ukrainian servicemen to release two detained militants—Serhii Hrytsenko, call sign Tiulen (Seal), and a militant wounded in the eye. In an interview, Azov fighter Andrii Dzyndzia said that the detained Tiulen had been released when he had been taken to the National Guard base. He was mistaken—the fighters were let go right on the spot, without being taken to the base.

After the two militants were released at the request of the crowd, at around 1:35pm—2:00pm the Ukrainian forces finally left the area of the Police HQ. First, nearly a hundred of National Guard soldiers and the soldiers of the 20 territorial defence battalion went away, followed by the white Bohdan bus with curtained windows. The bus moves very slowly, at the speed of the soldiers. They densely surrounded it and went along. This may mean that the bus carried bodies of the dead, and all measures were taken to ensure that the pro-Russian forces would not take the bus over. When Ukrainian forces were leaving the site, the Police HQ was already caught by fire, including the ground floor. The building had burnt almost to the ground afterwards.

One should also recall the events that took place at the exit of the Ukrainian BMPs (1:05pm—1:15pm). On its way back, BMP No. 240 stalled once again at the same corner of Myru Avenue and Torhova Street where it had stalled earlier that day. The Ukrainian soldiers decided to abandon the armoured vehicle completely this time and not to tow it away. Inside the vehicle, there was ammunition, including 30mm shells for the main gun. When the Ukrainian soldiers left, the BMP was seized by the civilians, who started looting it. Someone accidentally pulled the trigger, and a shot of the 30mm gun stunned everyone around, hit the ground floor of the opposite building, where a Delta Bank office was located. The bank wasn’t opened that day, and shutters on the windows were lowered. Fragments of the bricklayer that were scattered around wounded a pensioner passing by. Later, pro-Russian activists towed the BMP No. 240 to the city council building, where it was burnt the next day.

Most likely, the crew of that BMP moved to BMP No. 205. It should be noted that three crew men sat right on its armour, holding on to the turret. There is a viral video of a BMP under the Ukrainian flag making a leap through an improvised barricade. It was BMP No. 200, and the leap took place through the barricade in front of the city council at 1:23pm, when the BMP column was already leaving the city. The barricade had been constructed in the same place where civilians had been trying to block the BMP that had entered the city just two hours before. However, little is known about another and not less desperate leap: At 1:26pm, the same barricade was tackled by BMP No. 205, which flew over it in a leap, carrying the soldiers holding firmly on to its armour, thus making a terrific stunt. This BMP was the last of the Ukrainian armoured vehicles, and finally left the city at about 1:30pm.

On May 9th, observers at Civic Solidarity (Memorial) visited city hospitals Nos. 1, 2, and 9, where the wounded had been taken.

● In hospital No. 1, 15 wounded people, including 6 security officers, had been taken.

● In hospital No. 2, only one man had been taken, who had been shot in the heart when he had been walking with the dog. He died.

● In hospital No. 9, around 15 wounded people were reported to have been taken.

● 10 people had been sent to an emergency care hospital. Three of them were in difficult condition—two with stomach wounds, one with a wounded leg. One man, a Ukrainian soldier wounded in the stomach, died.

As of May 9th, there were another three corpses in the morgue, so the total number of deaths known to the observers was five; on May 10th, it increased to 10.

On 15 May 2014, the list of the names of the dead was published in Mariupol news media, which is almost accurate today. It had the names of 13 people, although mentioned a man with the name Vorobiov twice. The list also does not contain the name Zabovskyi. Thus, 13 names of the dead are known today.

It is likely that there were 14 dead people: On May 14th, a burnt body was found at the scene of the fire. It could belong either to the 14th unidentified person or to Serhii Demydenko, which will be explained below.

1. Viktor Saienko (born 1972, 41 y.o.), the head of traffic police of Mariupol. He attended the meeting at Andrushchuk’s office. Saienko’s body was found in the backyard of the Police HQ, but Ukrainian forces, for unknown reasons, did not take it with them as they left the area of the building. The versions of the circumstances of his death differ significantly.

2. Mykhailo Yermolenko (born 1976, 37 y.o.), a warrant officer of the Police, the patrol service.

According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the SBU, Saienko jumped out of the window; the SBU claims that he was trying to call for help, whereas the Ministry of Internal Affairs asserts that he was escaping from a militant. Yermolenko was wounded inside the building, on the flight of stairs leading to the second floor, and subsequently fell out of the same window where Saienko “had jumped” from. Together with Saienko and Yermolenko, several other employees of the Police HQ also fell out of that window, too. Both the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the SBU claim that most of the fallen people jumped deliberately and that Saienko was shot dead in the yard and died later on.

This, of course, looks odd, since there are much more discrepancies and inaccuracies than explanations. According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, at least six people fell out of the window—Saienko; later Pivovarov; then Yermolenko, without mentioning when; two unnamed men who retired later; and at least another person. The Ministry of Internal Affairs claims that Yermolenko fell due to the fact that he had been wounded and was unable to stand due to the loss of blood. However, this does not explain how the wounded Yermolenko spent at least two hours in the building before the fire broke out, and how he reached the open (or broken?) window and fell out of it. Also, none of the versions explains why other people continued to jump when they were shot at from below. The SBU claims that Saienko was about to call for help, although in order to do that, it was not necessary to jump anywhere—one could use a mobile phone. The Ministry of Internal Affairs explains that this was done in order to escape from the shooting, which is also unlikely since one would not just jump into the place where they are being fired from.

All the more strange it looks in the light of the fact that employees of the Mariupol Police HQ began jumping from the second floor not on May 9th. In an interview, Andrushchuk said that something similar had happened on May 7th, when commander of the patrol service company Zinoviev had jumped from the second floor, suffered bone fractures, and eventually fled to Crimea.

Given these circumstances, it can be assumed that the assault on the Police HQ by the militants was not entirely their sole initiative. Most likely, some employees of the Police HQ acted together with the militants, knew about the planned meeting, and planned their actions with the militants. The assault of the militants began almost synchronously with the start of the meeting, with some Police HQ employees siding with the militants and trying to capture all Ukrainian officers present at the meeting. Perhaps the resistance was not even expected, but the plan failed. The shootout started, the first wounded, and the few traitors from the police began to escape. It is not known why they decided to escape through the window—perhaps they could not leave the building in some other way due to gunfire, and it was possible to escape only by jumping onto the street.

There had been reports about traitors in the ranks of employees of the Mariupol Police HQ before. They are indirectly confirmed by the Ministry of Internal Affairs Col. Serhii Kolesnyk, who noted that in 2014, 188 people left the Police of Mariupol and were replaced by “more patriotic ones”.

There is also the reason why the traitors were not officially recognised as such. It could be either a purely humane desire not to spoil the lives of the families of the dead, or a more pragmatic consideration, as a way to silence the incident so as not to compromise the police, or to gain loyalty of the employees of the police and residents of Mariupol who would have condemned the tough reaction to the actions of the Police HQ employees, who had simply “made a mistake” by siding with pro-Russian forces.

3. Serhii Demydenko (born 1972, 41 y.o.), Lt. Col., deputy commander of the 20th territorial defence battalion. Col. Mykola Poboinyi (Ministry of Internal Affairs) said that Demydenko had been wounded in the leg and died of the loss of blood. It was alleged that the sniper had been in a nearby building, which could not be independently verified. The sniper could have hit him in the leg from a higher point which could not be found in the nearby area: In a documentary film, Hromadske TV of Pryazovia showed a hypothetical roof where the sniper could have been located, but not only is it too low in relation to the second floor of the Police HQ, but also the visio is essentially blocked with trees, so the version involving the sniper looks unconvincing. The EuroMaidan community mentioned Demydenko and the unknown body found on May 14th at the scene of the fire as separate casualties, but it seems they were the same person. Most likely, the body of Demydenko remained in the Police HQ, and was struck by fire, since the identification of his body was completed only in June 2014. The death of Demydenko was known from the witnesses of his death—police officers and the Armed Forces soldiers, but the body itself was not collected at that time, and a person in such cases may be considered missing in action. However, there is a possibility that the body mentioned in the May 14th report does not really belong to Demydenko, and thus, the total number of those killed on that day increases to 14 people.

4. Oleh Eismant (born 1974, 39 y.o.), a soldier of the 20th territorial defence battalion. He was wounded in the stomach, sent to the Mariupol emergency medical service, but died. The time and place of the would remain unclear. A local news media outlet reported that Eismant had been carried on the door, but this is not correct: The wounded soldier who was carried on the door was Oleksandr Kondrashyn, an Azov fighter.

5. Bohdan Shlemkevych (born 1993, 21 y.o.), a senior soldier of the 45th National Guard regiment. At about 10:20am-10:25am, he was moving with his unit towards the seized Police HQ along Heorhiivska Street from Hretska Street. The unit was met with dense fire; Shlemkevych’s bulletproof vest was pierced by three bullets, and he died on the spot from gunshot wounds.

6. Rodion Dobrodomov (born 1984, 29 y.o.), a soldier of the Azov battalion. He was killed at about 11:00am while clearing the courtyard of the Police HQ. Dobrodomov’s body was not taken away by the Ukrainian forces for unknown reasons as they left the area.

7. Oleh Koloshynskyi (sometimes referred to as Kolosnytskyi; born 1967), a resident of Mariupol who appeared on the fire line between a pro-Russian shooter with a pistol and a Ukrainian soldier at about noon in a shootout near Cafe Arbat. He was wounded twice in the leg and head, and subsequently died. It was reported that he had saved a wounded journalist of Russia Today (RT), but this is not true: Koloshynskyi did not save anyone, but was just a passerby who watched the events. The freelance journalist of RT was wounded in Heorhiivska Street, near the intersection with Metallurhiv Avenue, i.e. 2 to 3 blocks away from the shootout.

8. Oleksii (named Leonid in some sources) Vorobiov (born 1975, 39 y.o.), a resident of Mariupol who was injured near the Police HQ. According to one version, he was walking a dog nearby. According to another version, he had his own shop near the Police HQ, was wounded and sent to the hospital, but doctors could not save him.

9. Petro Yelisieiev (born 1976, 38 y.o.), a pro-Russian militant who died from a gunshot wound during the assault on the Police HQ. According to the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Group, he was a resident of Mariupol; other sources claim that he had Russian citizenship, and even fought in Egypt earlier.

10. Mykola Kushnir (born 1961, 53 y.o.), a pro-Russian militant who died in the Police HQ of numerous gunshot wounds, of which the forensic pathologist counted at least 38. Before his death, he sent his relatives the following text message: “I am wounded, we are barricaded in the Police HQ.” Perhaps he was locked up wounded in the gun room and was killed when the building was purged by Omega specOps officers. This could explain numerous wounds as a result of a short distance firefight, when the officers opened the gun room. The militant Serhii Hrytsenko, call sign Tiulen, said of those events:

“…A few moments later, a fighter was brought from the ground floor with a wounded eye. He said that a grenade had been thrown from the street, he did not manage to throw it away, but he managed to close the door to the gun room, where N1 and N2 were, so that they would not be wounded. Therefore, the door to the gun room closed, and the said people could not escape from it.”

11. Serhii Drozdov (born 1982), one of the pro-Russian militants who took part in the assault on the Police HQ, a resident of the village of Talakivka. He died of a gunshot wound in the chest in the building. He was the second militant who was locked up in the gun room. According to the testimony of Serhii Hrytsenko, call sign Seal:

“…a guy was found, subsequently, dead in the gun room of the Mariupol Police HQ. If I am not mistaken, [it was] Serhii Drozdov.”

12. Hennadii Zabovskyi (born 1961, 52 y.o.), who died of a gunshot wound in the Police HQ. According to local news media and Russian sources, he was one of the pro-Russian militants.

13. Garnik Arzumanyan (born 1967), perhaps a citizen of Armenia. Archbishop Grigorys Buniatyan, the head of the diocese of the Armenian Apostolic Church of Ukraine, said of the circumstances of his death:

“During the clashes, [during] the fight, he was hit on the head, and the man subsequently died.”

Priest Ter Usik Nuridzhanyan said that Arzumanyan had died of a blow on the head. Arzumanyan was buried in Armenia, which gives reason to believe that he had Armenian citizenship. The circumstances of his death are not known. Some Russian sources suggest that the cause of his death could have been a domestic conflict. However, the domestic nature of the causes of his death is unlikely: The body was found in the area of clashes in the city, and Grigoris Buniatyan, commenting on the death of Arzumanyan, also added:

“We urge the Armenians to maintain neutrality, and who, by their own decision, joins one side or another, does it on their own.”

This sounds like a cautious answer to a very delicate question, namely, a way to inform that Arzumanyan indeed sided with one of the parties to the conflict. No details on which side exactly.

Thus, according to the official version, the death toll included six people on the Ukrainian side, two civilians, and four militants who participated in the attack (the circumstances of Arzumanyan’s death are yet to be clarified). If there is direct evidence that Saienko or Yermolenko sided with pro-Russian forces, this would also make the appropriate adjustments to the general picture of the events of May 9th.

Russia’s state Pervyi Kanal (The First Channel) reported that the army had opened fire at the peaceful people who had come to defend the militants:

“Right from the festivities, they went to the Police HQ to defend the barricaded police officers. And then, something that was most feared happened: According to self-defence forces, the army opened fire at the peaceful people, shooting to kill. Meanwhile, in another district of the city, people in black uniform started shooting at the participants of the rally, where there were families with children and no political demands.”

This message was repeated in various forms:

3:49pm: “…the military opened fire at the unarmed people, it is known […] that two people are dead”;

4:37pm: “…with a call for ceasing violence, people began to gather around the police office, the military opened fire at the unarmed people”;

10:14pm: “Snipers killed civilians who stood in the street […]. The so-called ‘National Guard,’ who in fact are war criminals, are killing their own people”;

10:16pm: “…at about half past ten in the morning by local time […] armoured vehicles entered the city. Eyewitnesses say that those who stood on the way of the column were shot at right from the armoured vehicles without lowering the speed. […] Military gunmen of the so-called ‘National Guard,’ that is, the armed Right Sector, shot at the unarmed people to kill. […] Police officers were killed in Mariupol—those who refused to execute criminal orders. […] According to eyewitnesses, the building [of the Police HQ] was shot for more than an hour. As it became known to us from unofficial sources, the police officers were ordered to shoot at their own citizens at the rally on the occasion of Victory Day. They refused, and it was decided to deal with them in this way.”

Russian media had distorted a number of crucial facts: from whom were police officers barricading, who started the gunfire, when and why. They even added the absurd accusation that, while retreating, the National Guard had fired a grenade launcher on the streets of the city. But those “inaccuracies” pale in comparison to an outright disinformation about intentional murders of the unarmed, and about the order to shoot a peaceful march, including children.

It is important to emphasize that this propaganda piece was broadcasted not by some obscure outlets but by the federal TV channels of the Russian Federation to a hundred million people. Moreover, it was broadcasted on 9th May—a Victory Day, one of the most respected holidays in Russia. If one should take everything the Russian leading news channels reported at face value, the Ukrainian Army and the National Guard really would look like a group of utterly depraved thugs. This is the whole point of wartime propaganda—to invoke hatred towards the enemy. Russia as a state had systematically resorted to such methods, waging an information warfare against Ukraine as one of the aspects of an ongoing military aggression. The crucial role of this propaganda in instigating a war cannot be overstated—it was necessary to stir up indignation among Russian citizens and create an image of Ukrainian enemy—a vile, miserable, and not worthy of pity or compassion. Russian federal media formed their parallel world, preparing their audiences for the war and explaining its, albeit made up, reasons.

Russian puppet republics also offered their take on the events. In 2016, the “Ministry of Information of the DNR” released its “documentary film” about the events in Mariupol on May 9th. What is striking about this film, is that the puppets do not hesitate to lie about completely absurd things. And while the outright lie of the Russian news media during the outbreak of the conflict in 2014 could be explained by the need of the aggressor state to occasionally stir up the said; the need to rehash said messages in the “DNR” two years later, with the events long gone, when it’s time to analyse them rationally, can be explained by the fact that the creation of an image of the “DNR” and their “Ministry of Information” as a reputable source of information was never an objective of neither their Kremlin bosses nor themselves.

Here is a breakdown of one striking example. At the 20th minute, an unnamed narrator states that an abandoned BMP No. 240, which, at that time, was then overtaken by civilians, fired a shot:

“…But this BMP managed to shoot at a house. A family died.”

The narrator’s utter cynicism is striking: the outright lie about the whole family’s death was told in an absolutely unobtrusive manner—the shot hit a bank’s office, which wasn’t even open that day, not the apartment building. At the end of the film, the list of victims was shown, but “DNR” didn’t bother to back their lies—there was no dead family in that list. That is, to blatantly lie in a so-called “documentary” film about such a serious accusation as the murder of an entire family is a routine task for Russian puppets.

Afterword

On 9 May 2014, civilian witnesses took almost all of the events in the city through the distorted prism of rumours. It is clear from the vast majority of materials that the residents were convinced that the Ukrainian army and the National Guard had allegedly come “to punish policemen who stood on the side of the people and refused to shoot at the parade.” The absurdity of such assumptions was the most striking in the following vivid example. At 1:22pm, policemen in uniform came from the yard of the Police HQ and started talking with the National Guard and Armed Forces soldiers. A young man with pro-Russian sentiments, who had been recording video of the events for half an hour already and commending the actions of the militants in the building (“Our police, our native police; our boys; policemen resist, good guys”), suddenly said of the above mentioned policemen:

“And just who the hell are those bacons?”

He could not paint the picture where the police had never really been the target of the Ukrainian forces, had not betrayed Ukraine’s oath, and all the events in the city were the result or a consequence of the actions of a diversion group of pro-Russian militants who had tried to seize an important object to control Mariupol.

Over the next few months, the SBU and the police detained half a dozen militants that managed to hide in the crowd during the events of May 9th, thus avoiding punishment. Another ten people, headed by Oleh Nedavnii, call sign Mongoose, were wanted as of 2015.

Read also:

The contents of the article are licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. Copyright exceptions are marked with ©.

The article was prepared with the assistance of the Ministry of Information Policy of Ukraine.

Підтримати нас можна через:

Приват: 5169 3351 0164 7408 PayPal - [email protected] Стати нашим патроном за лінком ⬇

Subscribe to our newsletter

or on ours Telegram

Thank you!!

You are subscribed to our newsletter