Dmytro Putiata, Andrii Karbivnychyi, Vasyl Rudyka

Since 1992, Ukraine had been consistently downsizing its Armed Forces. The reason was that Ukraine’s economy could not afford to maintain a large military force inherited from the Soviet Union, which used to be part of the second defence line behind the Soviet troops deployed in the Warsaw Pact countries.

That force included 21 divisions, three air armies, an air defence army, and other military units, which in total amounted to 980,000 troops—meaning that they had been designed for imperial purposes and doctrines and were excessive for newly independent Ukraine, especially given the economic crisis of the 1990s. As the Cold War ended with the Soviet Union’s defeat, there was no ideological grounds for having so many troops either. Hence, Ukraine proclaimed a policy of neutrality and non-alignment, with its Armed Forces engaging in peacekeeping missions under the auspices of UN agencies.

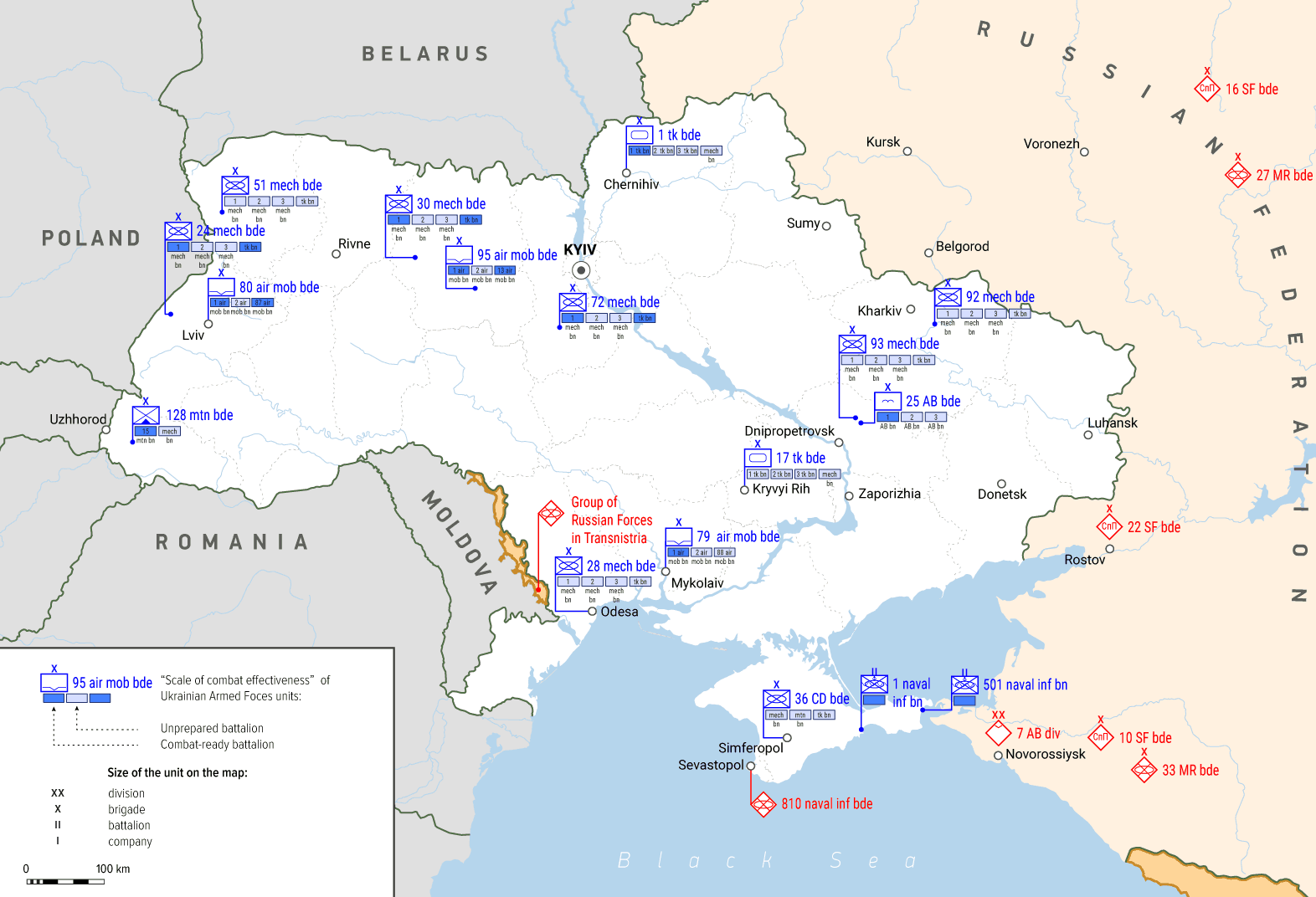

By inertia, the deployment of the military units of the Armed Forces inherited after the Soviet Union’s policy towards its “aggressive neighbour”—NATO member states. It is in western and northern Ukraine that the largest number of troops with decent training and operational capabilities was amassed. These included:

In central and southern Ukraine, the following units were deployed:

In Crimea, the following units, of which marine infantry was fully operational, were deployed:

In eastern parts of Ukraine, the following units were deployed:

The Donetsk and Luhansk regions had no Army or Airmobile Troops units of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Instead, Internal Troops units were deployed in Luhansk, Donetsk, and Mariupol, as well as an Air Defence unit outside Donetsk.

On and about 20 February 2014, Russian forces started a military operation to take Crimea under their control.

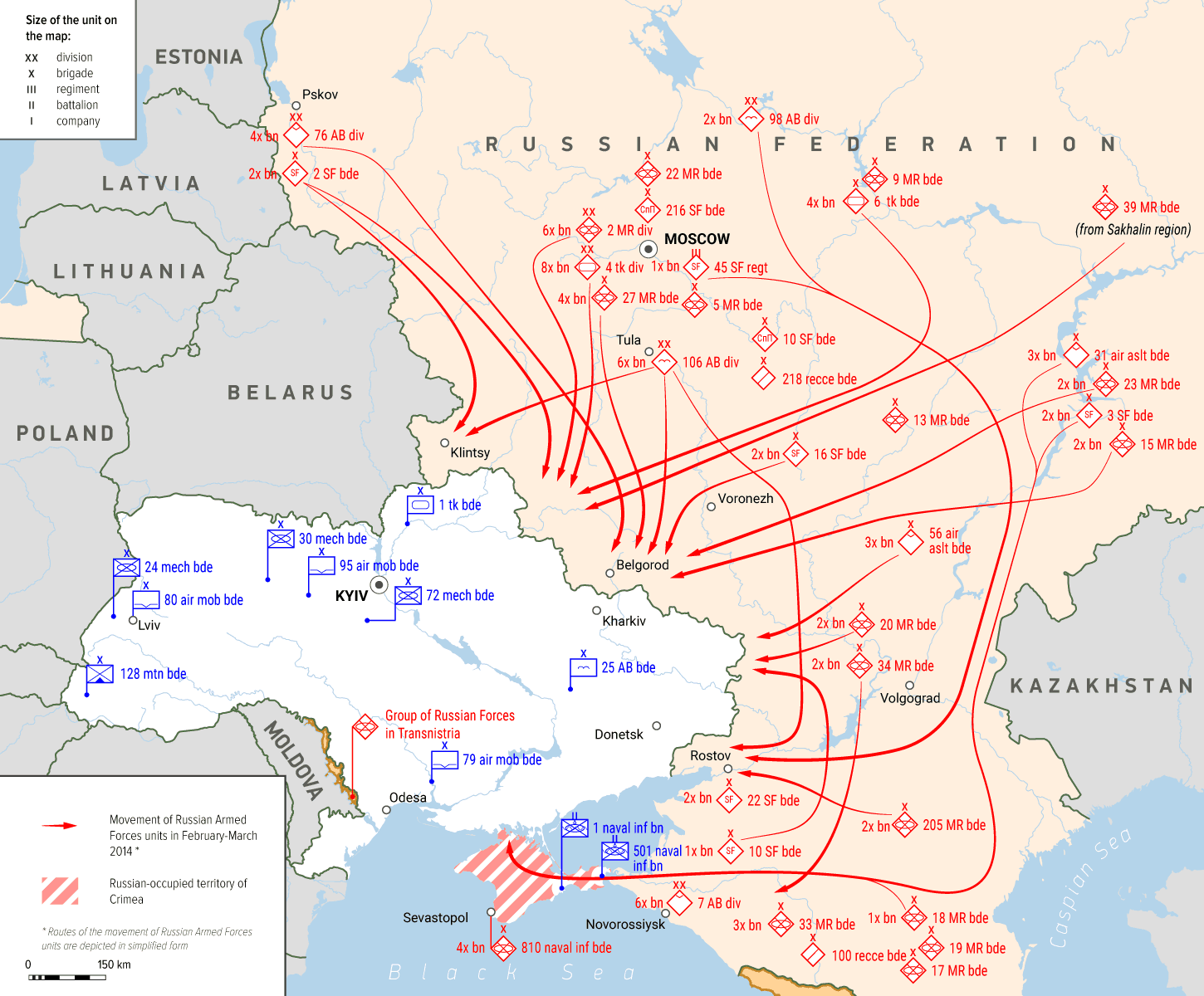

On 26 February 2014, Vladimir Putin suddenly launched large-scale snap exercises in Russia’s western regions, including those directly adjacent to Ukraine. At 10:00am, troops in the Western Military District and parts of the Central Military District, Airborne Troops and transport aircraft were raised on alert. Russia’s Defence Minister Sergey Shoygu reported that the forces had been alerted by 2:00pm MSK. According to the official plan, deployment on the local firing grounds was to take two days, and as of February 28th, battle exercise was to start, involving the 6th and 20th armies of the Western Military District, the 2nd army of the Central Military District, and Airborne Troops. In early March, the exercise already involved around 150,000 troops, more than 90 aircraft, 120 helicopters, up to 880 tanks, 1200 other military vehicles, and up to 80 ships and vessels. Official sources reported that 38,000 military personnel of the Army, the Marines, and the Airborne Troops were participating in the exercises in the European part of Russia. In March 2014, various sources in US, European and Ukrainian security services put the figure at 35,000 to 220,000 troops, suggesting that the exercises were posing a military threat to Ukraine. The difference can be explained by methods of calculation, which vary depending on whether they include forces at the Ukrainian border alone, or in each territory where the drills were held—including the Baltic and Black Seas and further into the Asian part of Russia—and whether they are based on Russia’s official data, or intelligence reports.

Given the feebleness of the Ukrainian government, or, putting it more bluntly, lack of government as such (heads of virtually all Ukrainian security institutions fled to Russia after Yanykovych’s regime collapsed), the Kremlin used its Armed Forces and Special Operations Forces to seize control over the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and further annex it.

On the night of February 26th to 27th, Russian special operations officers seized the building of Crimean Parliament. On February 28th, Simferopol International Airport and the Belbek military airfield outside Sevastopol were seized. On 1 March 2014, President Vladimir Putin of Russia requested the Federation Council (the upper house of Russia’s parliament) to permit using forces in Ukrainian territory. This request was essentially formal, as the military operation had already begun, and Russian troops were already carrying out military operations in Ukraine. On the same day, the Federation Council unanimously approved the request, with all the senators present voting in favour. Curiously enough, during the voting the number of senators in the hall was ranging from 78 to 90, with 84 required for quorum (slightly higher than half of the total number of 166): since it was an emergency meeting, some of them were late, and the voting system was acting up, so the number of those present could not be counted correctly. Whether parliamentary procedure was followed and, consequently, the decision was legitimate is an open question. In the final analysis, however, the legitimacy of the decision does not matter, only adding a few strokes to the picture of the events in the spring of 2014. In fact, in 2009, Russia’s Law “On Defence” was amended, giving the President authority to use armed forces abroad without the Federal Council’s approval—as was mentioned earlier, Russian troops were already carrying out missions in Ukraine when Putin submitted the respective request to the Council. It was, therefore, more of an image move to show that Russian politicians supported Russia’s military action against Ukraine.

How the Russian Federation prepared for and carried out its intervention into and annexation of Crimea, and the circumstances surrounding it, is a complex task that requires detailed research. Some of the aspects of the intervention can be considered to have been worked out in advance by Russia or to have played into its hands—the precarious state of Ukrainian forces and Russian agents and pro-Russian mood among senior military commanders. Other facts, though, make it possible to suggest that not everything had been calculated beforehand, and Russia had to “wing it.” The referendum in Crimea, which had originally been planned for May 25th, was brought forward to March 30th, and later to an even earlier date—March 16th. It was clear that there was ridiculously little time to organise such an important process. Therefore, such a hurry clearly suggests that Russia was finding its “window of opportunities” to act narrowing rapidly.

The lack of military insignia on Russian troops and Russia’s tampering with the “grey area” of international law was, too, indicative of the weakness—not the strength—of its position. While formally denying the use of forces, Russia reserved the position of plausible deniability and room for manoeuvre. At any given moment, the Russian government could call off the operation without losing face or, conversely, resort to force and bear no responsibility therefor. Apart from doing away with insignia, the military “trump card” could have been used in a variety of ways. “Green men” in Crimea behaved provocatively and arrogantly, so it makes sense to assume that the Russian leadership was considering the option of Ukrainian forces in Crimea resisting the occupation, resulting in casualties. This could have been followed up by Russia accusing the new Ukrainian government, which had not yet been internationally recognised, of bloodshed, and launching a full-scale military operation. It would have resembled how the events of the 2008 Russian-Georgian war unfolded and may have been one of the options for using the forces that had been deployed at the Ukrainian border. “Peace enforcement” could have led to a rapid offensive on Kyiv or seizure of the entire southern east of Ukraine.

One way or another, at the time Russia could not officially admit its involvement in the military operation against Ukraine due to numerous reasons—both domestic and external. The Ukrainian government, in turn, also had to act carefully, since the country physically could not fend off the enemy’s all-out onslaught and since the provisional government had not been elected by the people. Such vagueness and restraint, exercised by both the aggressor and the defendant, added to the complexity of the situation, making it difficult to people in the two countries to make up their minds, and fuelled the feelings of artificiality and incredibility—even surreality—of what was going on. Despite the evident act of military aggression, there were no combat operations, and war or martial law was not declared.

A separate issue is analysis of the decisions taken—what Russia had in mind when committing an act of aggression to claim the territory of another state in the 21st century. Whatever the reasons, Russia has created powerful leverage over Ukraine, which has lost much room for decision-making and has been having to deal with an open-ended territorial conflict.

In late February 2014, Ukraine suffered a nearly complete collapse of the highest military-political leadership. All heads and commanders of security, defence and law enforcement agencies had fled to Russia, including:

Yurii Illin, the Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces appointed in February 2014 by Yanukovych, was sabotaging the Commander-in-Chief’s orders. In May 2014, he deliberately moved to Russia-occupied Crimea.

Denys Berezovskyi, who was appointed new Commander of the Naval Forces on 1 March 2014, openly sided with Russia the very next day, on March 2nd, and started encouraging Ukrainian officers to follow suit.

The size of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, let alone their operational capabilities, did not allow defending the state in any possible direction of attack. On 11 March 2014, Acting Minister of Defence of Ukraine Ihor Teniukh reported that only 6,000 Army troops out of 41,000 were operational. And there were more than enough directions of attack to defend—the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the regions of Sumy, Chernihiv, Kharkiv, Donetsk, Luhansk, and Odesa (from the Transnistria, where a Russian contingent of soldiers was permanently stationed).

On 17 March 2014, the day following the Russia-orchestrated referendum in Crimea, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine passed a law on partial mobilisation. It began the next day, on March 18th, when the Kremlin set up a ceremony in celebration of Crimea’s reunion with the Russian Federation. Mobilisation turned out to be quite a problem for Ukraine—it could not be handled appropriately because of the precarious draft system. Apart from there not being enough draft offices, the system was plagued with red tape: It was common for Ukrainian volunteers to turn up at a draft office, which for various reasons could not assign them to regular military units. Those who were most motivated joined spontaneously created volunteer formations, which were to be completely incorporated into state structures later on.

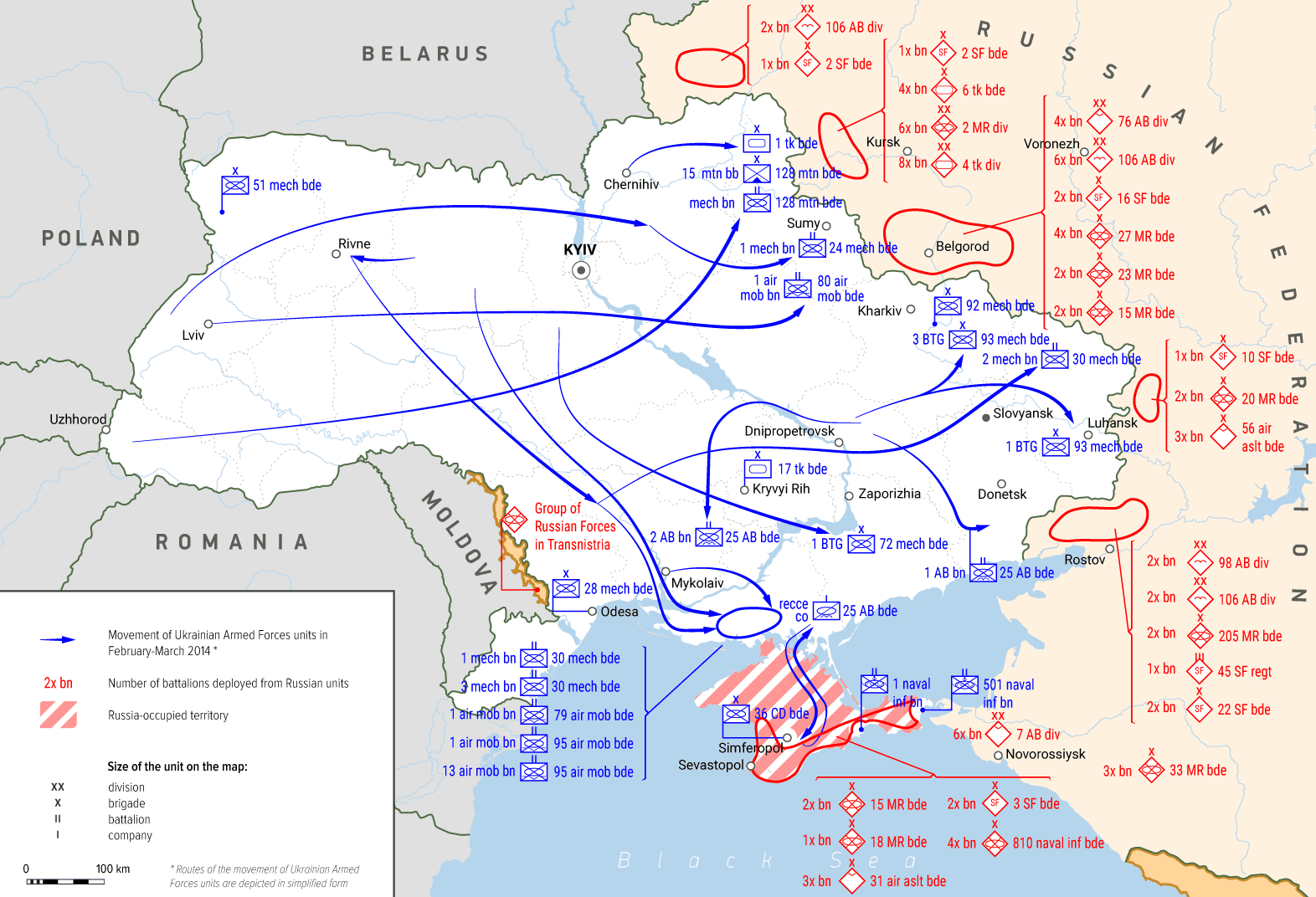

Military units of Ukraine’s Armed Forces were put on high alert after the Russian military intervention into Crimea started.

They included, first of all, special forces and Airmobile Troops, which had the highest operational capability.

In general, each brigade in Ukraine’s Armed Forces wasn’t able to provide more than one operational battalion, which constituted the image of the entire Armed Forces. In the 24th separate mechanised brigade, it was the 1st mechanised battalion; in the 25th separate airborne brigade, the 1st airborne battalion, which had been regularly taking part in military drills; in the 95th separate airmobile brigade, the 13th battalion, which had participated in international exercises (the 1st battalion was in fact on a par with it); in the 80th separate airmobile brigade, the 1st battalion; and in the 30th separate mechanised brigade, the 1st battalion. The 54th and 74th reconnaissance battalions performed well, too. They all constituted the operational Armed Forces of Ukraine at the time—with most troops in the units being contracted soldiers.

Aviation forces played their part, too. Again, most operational army aviation helicopters, namely in the 7th separate army aviation regiment and the 16th separate army aviation brigade, were deployed in Western Ukraine (Novyi Kalyniv and Brody, respectively). Helicopters of the 11th separate army aviation brigade (Chornobaivka, Kherson region) also engaged in combat as the conflict evolved. In total, there were no more than 15 Mi-24 attack helicopters. The spring exercises and the following combat involved Su-25 attack aircraft, with no more than eight of them being operational. The same held true for Su-24M bombers. Therefore, as of March-April 2014, the total number of operational military equipment in the entire Armed Forces of Ukraine included:

These would have been enough to tackle illegal armed groups, even supported by several units of Russia’s Armed Forces. However, would it have sufficed in the case of a full-fledged onslaughts of Russian forces in the spring of 2014? Given the length of the Ukraine-Russia border, the answer is no.

When Russian forces started manoeuvring and deploying at the border with mainland Ukraine and in the Crimean Peninsula, special forces units were the first to be alerted in Ukraine’s Armed Forces. As they were adequately staffed, those units were among the few operational in late February 2014. The 3rd and 8th regiments were given various tasks, most of which are still classified. Separate special forces regiments were deployed in the Kharkiv region (3rd separate special forces regiment), in the Sumy region (8th separate special forces regiment), and at the border with Crimea, where they gathered intel and monitored the movement and exercise of Russia’s Armed Forces at the Ukrainian border. The 8th regiment, in addition, was tasked with evacuating secret equipment and accompanying important transfers from the Kharkiv region. In March, some groups of the 8th regiment were deployed in Crimea, albeit too late: most Ukrainian units and military bases were already controlled by the occupant at the time. At first, those groups were dislocated in Perevalsk, from where they moved back to mainland Ukraine later on.

In late February, a reconnaissance company of the 25th airborne brigade, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Mykola Palas, moved to Crimea for military drills near Perevalne. The company managed to return to mainland Ukraine with all the equipment and armaments after Crimea was annexed.

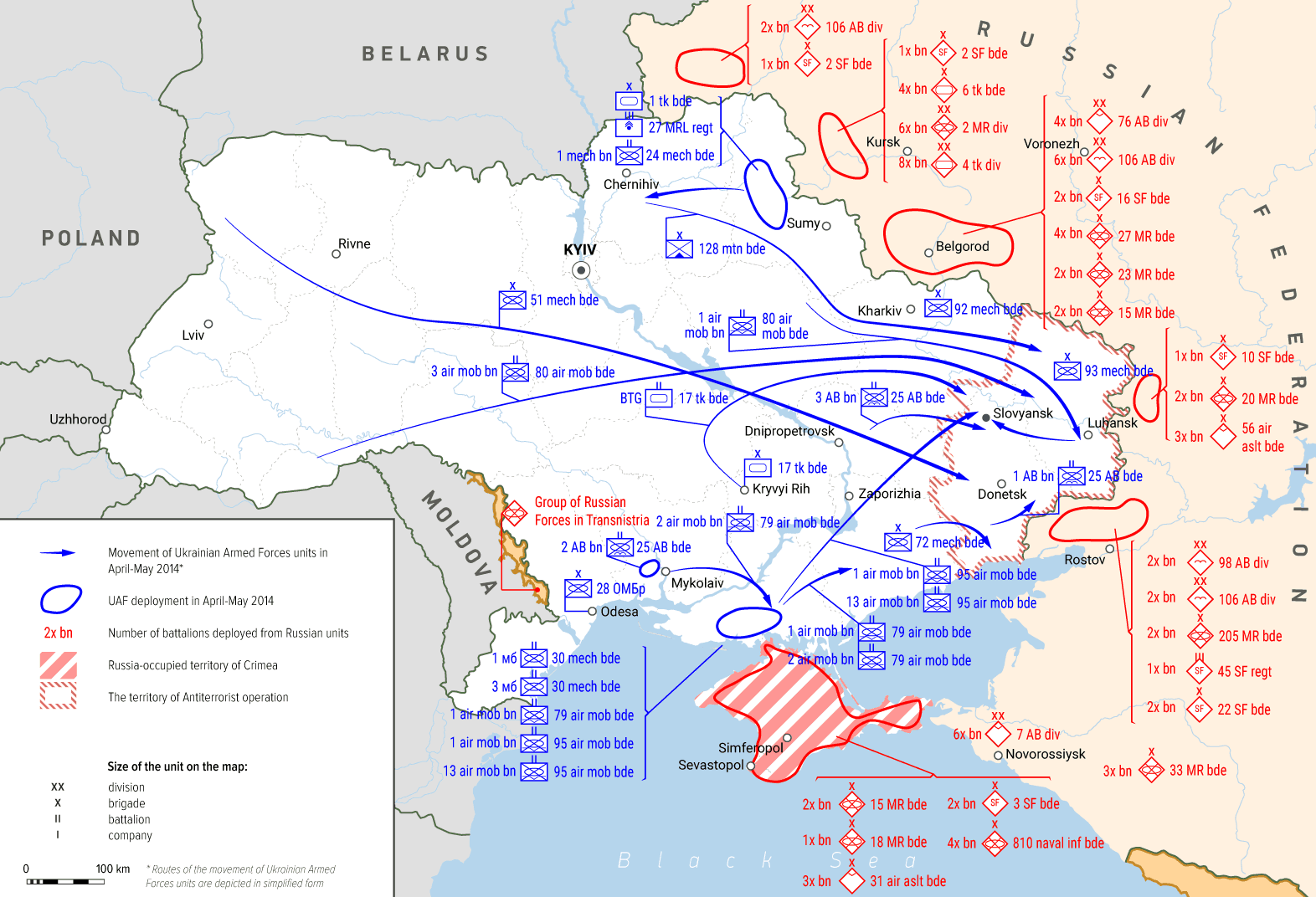

The reduced 1st battalion of the 25th separate airborne brigade, where most servicemen were contracted soldiers, supported by a 2S9 “Nona” SPG battery, was sent in March 2014 to the border with Russia in the Donetsk region. In April it received additional reserved soldiers, and had stationed near Amvrosiivka. The battalion stayed at the Russian border until June. After a battalion tactical group was formed on the basis of the 2nd battalion, part of it was deployed in the Kherson region, and the other part on the “Shyrokyi Lan” firing ground outside Mykolaiv. The 3rd airborne battalion was formed entirely of mobilised soldiers, except for the commanders. After Igor Girkin’s group appeared in Sloviansk, the battalion, supported by a self-propelled artillery battery, was dispatched there on April 12th or 13th.

The 79th separate airmobile brigade was alerted on March 2nd. More accurately, it was only part of the 1st battalion, where, as well as in a reconnaissance company, contracted soldiers were serving. The unit was sent to the Kherson region, near Chaplynka. There was a plan to redeploy the units in Crimea to secure a roothold in several northern Crimean localities. Major Dmytro Marchenko, one of the brigade’s officers, drove a civil vehicle to Armiansk to size up the situation. Reconnaissance revealed that the main highway in the city was already under the control of armoured personnel carriers of Russia’s intervention forces. The plan was cancelled, and so the battalion stayed. Later, its forces were rotated. In late March, the 2nd battalion was formed with mobilised troops. As of April 18th, the fully operational 1st and 2nd battalions were in the Kherson region; on May 18th, they were sent to the Zaporizhzhia region, and in June, to the Donetsk region. Another battalion within the brigade, the 88th, stayed in the Odesa region, did not get engaged in combat due to lack of servicemen as well as equipment.

The 95th separate airmobile brigade was alerted in March, too. Some of its troops were deployed in the Kherson region: although the 2nd battalion was already deployed there, only the 1st and 13th battalions of the 95th brigade were immediately operational. The brigade was justly considered one of the best. After manoeuvres near Crimea, the battalions were sent to the Donetsk region. It is only in early March that the 2nd battalion, manned with mobilised soldiers, was deployed in the combat area in Donbas.

In the spring and summer of 2014, the 80th separate airmobile brigade consisted of the 1st and the 3rd battalions in Lviv and Chernivtsi, respectively. The 1st battalion, mostly manned with contracted soldiers, was an operational unit, although instead of 30 standard armoured personnel carriers it had only just above 20. The 1st battalion was deployed in Poltava and Sumy regions in March. On April 8th a battalion’s airmobile company secured Luhansk airport. After Girkin’s group came, some of them were deployed outside Sloviansk.

The brigade was not an ordinary one. Whereas airmobile brigades normally have 18 D-30 howitzers, the 80th brigade had nearly 30 of them. The 3rd battalion was considered a separate unit with its own division and reconnaissance and support companies. No sooner than in March was it fully manned and sent to the Luhansk region. The 2nd battalion, also stationed in Lviv, was mostly not engaged in combat until late August.

Rocket artillery regiments were able to provide only one division each (later, this number tended to increase). In March and April, the 26th artillery brigade dispatched a division of 2S5 and 2S19 SPG each to the firing ground, where they held joint combat training with other brigades. Two SPGs were lost due to a violation of safety regulations.

The 107th rocket artillery regiment, equipped with deadly BM-30 “Smerch” heavy multiple rocket launchers, was alerted in early March and supported other units along the Russian border. Later, it was deployed near Crimea for exercise.

The 27th rocket artillery regiment, equipped with BM-27 “Uragan”, was deployed in Sumy. Due to the near Russian border (34km away), as early as March 1st it was fully dislocated in Myrhorod, Poltava region. As the Ukrainian forces deployed, the regiment supported mechanised and tank units at the border.

The 55th separate artillery brigade was able to provide only two batteries. One of them was equipped with outdated D-20 howitzers, the other had Msta-B howitzers. Both batteries moved to the border area. In late June, another Msta-B battery was formed by the brigade.

As rapid reaction forces were deployed, battalion tactical groups (BTGs) of mechanised and tank brigades were formed with mobilised soldiers, which took quite a lot of time.

In the 24th separate mechanised brigade, a BTG was formed in early March on the basis of the 1st battalion, where many contracted soldiers were serving. The battalion was fully equipped and supported by four 2S3 “Akatsiia” SPGs, six BM-21 “Grad”, a 120mm mortar battery, a tank company (10 vehicles), a reconnaissance company (with APC-80 and BRM-1K), and engineer and logistics units. This BTG was quite operational and capable of engaging in offensive and defensive combat, as the summer campaign showed. On around April 7th or 8th, the BTG moved to the Chernihiv region and later, to the Sumy region, where it stationed with the 27th rocket artillery regiment and the 1st separate tank brigade to cover the dangerous border area from Russia’s possible intervention. From there, the 24th mechanised brigade moved to the Poltava region, and then to the northern Luhansk region, where it set up checkpoints and stationed for more than a month. Later on, it was deployed near Sloviansk following the beginning of the combat. Although the 2nd BTG of the 24th brigade was formed as far back as April 2014, it seemed to have been on a stand-by and was deployed to the border area only in June. The 3rd BTG was sent to the combat area in Donbas only on July 10th.

In March, a BTG of the 1st separate tank brigade was formed with mobilised soldiers. Two tank battalions, a mechanised battalion, a reconnaissance company, a 2S3 “Akatsiia” SPG battery, and “Grad” batteries were amassed. It should be noted that the organisational structure provides for 18 vehicles for each artillery division, but due to lack of personnel who could man those vehicles only a battery (6 vehicles) was formed in 10 days. In April-May, the units were additionally manned, and divisions (albeit not all of them) got 12-14 vehicles in total. The 1st separate tank brigade, as was noted earlier, was stationed in the Cherтihiv and Sumy regions, where it exercised and oversaw the prospective front area. Later, it was fully deployed in the northern Luhansk region. Given that almost all the troops in the brigade had been mobilised, its operational capability was rather poor, as the combats that followed proved.

The 30th separate mechanised was alerted on 1 March 2014. On March 8th to 9th, all three battalions moved from the permanent station to firing grounds in the Rivne region and the “Shyrokyi Lan” firing ground in the Mykolaiv region for two weeks. The size of the brigade (around 4,000 troops) made it one of the largest at the time. However, only the 1st mechanised battalion was mostly manned with contracted soldiers, whereas the other two consisted of mobilised troops. In August, the 1st mechanised battalion proved its combat efficiency. After joint exercise with other brigades on the firing grounds, the 1st and 3rd battalions were sent to the Kherson region, close to the Crimean border, and the 2nd battalion to the Luhansk region.

On March 8th, the 72nd separate mechanised brigade was alerted. During March-April 2014, two BTGs were formed. On March 20th, the 1st BTG arrived in the Zaporizhzhia region, and on April 10th, another echelon of the brigade. In April-May, they ensured defence near Mariupol, and later on were dispatched to the border area. The 72nd brigade was the third largest brigade in the Armed Forces of Ukraine, though the lion’s share of its manpower consisted of mobilised soldiers.

The 128th separate mountain infantry brigade was alerted on March 2nd and sent to a firing ground. It included the 15th mountain infantry battalion and a mechanised battalion. The brigade was also undergoing reform: it used to have a tank battalion and a 2S3 “Akatsiia” SPG division. Due to the downsizing, two BTGs, a tank company and an unmanned “Akatsiia” battery (4 SPGs) were formed, which were sent to the Sumy region on May 18th. At first, they stationed in Konotop, and two weeks later were deployed outside Baturyn in the Chernihiv region. In early April, they again were dispatched to the firing ground of the 1st separate tank brigade, and in May, they moved to the Luhansk region.

In March-April, three battalion tactical groups of the 51st separate mechanised brigade were formed. As with other similar brigades, only a few troops and civilian personnel remained at the permanent station on a regular basis, who were supposed to prepare equipment and conditions for the other personnel in the event of war. Prior to the mobilisation, the brigade included around 500 soldiers, officers and civilian personnel. After the mobilisation, battalions were formed, and on March 12th, the 51st separate mechanised brigade moved to the firing ground, where it was manned and equipped until April. After being manned by mobilised soldiers, the brigade became the largest in the Armed Forces of Ukraine, and was later deployed in two regions, where it fought bravely. It was the only military unit with a 2S1 “Gvozdyka” SPG division (such SPGs had been withdrawn from service in Ukraine’s Armed Forces). In May, the brigade moved to Donbas, where it set up a line of nine checkpoints in the Kurakhove-Vuhledar-Volnovakha area. Although it was the largest brigade, 85 percent of its troops were mobilised, which affected its operability.

The 17th separate tank brigade, which was supposed to be the army’s powerhouse, was being disbanded at the moment. It was impossible for it to form a single tank battalion even in a month. In early March, it moved to the firing ground with little forces. On March 20th, fire broke out at the permanent station, destroying six tanks. It significantly affected the brigade’s operational capability—it could not even form a company tactical group. During April 10th to 17th, a few tanks and BMP-2 of the brigade were sent to Izium. By June, it could provide only 10 tanks, a few BMP-2, and a 2S3 “Akatsiia” SPG battery.

The 28th separate mechanised brigade managed to form the first (and the only one in the summer) BTG in March. On March 10th, an BMP-2 of the brigade was destroyed in the course of the exercise on the “Shyrokyi Lan” firing ground, with another 24 BMP-2 and 5 2S3 “Akatsiia” SPGs being damaged due to mismanagement of the equipment. The newly formed BTG in fact immediately became non-operational. Therefore, only one BTG with an added SPG battery could be formed on the basis of the 28th brigade, and it was deployed on the frontline border area as late as July 7th.

Although having the least military units, the brigades in the eastern regions showed the highest combat effectiveness.

In March, the 93rd separate mechanised brigade was sent to the Kharkiv region, whereas some of its troops moved to the northern Luhansk region. On March 15th, a column of vehicles was stationed near Stanytsia Luhanska, with some of them in Alchevsk. On March 17th, some units were deployed in the Kharkiv region; a month later, on April 17th, at the Russian border in the Luhansk region; in May, a checkpoint was set up in the Donetsk region on the Krasnoarmiisk-Dobropillia-Kramatorsk line. In general, the 93rd separate mechanised brigade was one of the best in Ukraine’s armed forces in terms of manpower and equipment.

The 92nd separate mechanised brigade did not manage to form a single operational unit, so it was not engaged in combat in Donbas. A few troops and some operational equipment within the brigade were deployed at the Russian border in the Kharkiv region. It is only in late August, during the fierce Battle of Ilovaisk, when a company tactical group based on the brigade was used as reserved forces.

Russian propaganda does not make a point of this period of the conflict.

The least informed and most biased Russian proponents claim that the first thing that the Ukrainian government did upon coming into power was the dispatch of tank echelons to Donbas. This most primitive argument suggests complete incompetence, empty rhetoric, or both. The timeline and regions of the deployment of Ukrainian forces dismiss this argument as utterly baseless and absurd.

Another point of Russian propaganda is mass evasion during limited mobilisation; as it says, thousands, if not dozens of thousands, of Ukrainian citizens were hiding from draft offices, or even fleeing to Russia. This asserts the opinion that Ukrainians were supposedly not intent on defending the Ukrainian state—and if its own citizens see no value in it, there can be no claims to Russia whatsoever. Indeed, limited mobilisation in Ukraine was faced with problems: as has happened earlier in history, there were cases of evasion. Russians, however, deliberately turned a blind eye on the powerful volunteer spirit of Ukrainians. As was noted earlier, draft offices had difficulties managing their work, and their codes of operation were not fit for limited mobilisation: not all enlisted were intent on going to war, and many of those who did want to do so were refused on formal grounds. Therefore, in order to have a clear picture of whether Ukrainians wanted to defend their country or not, one has to take into account all the aspects of the issue.

Russian propaganda also claims that Ukraine as a state did not dare fight against the real regular Russian army in Crimea. It holds true only in part—as of February 2014, Ukraine indeed was not ready for confrontation. Its task, however, was to choose such conduct which, firstly, could defend the sovereignty of Ukraine, and secondly, would eventually lead to victory. Therefore, direct confrontation was avoided for a number of good reasons. What escapes Russian propaganda in this regard is that, whereas Russian regular army forces were indeed deployed in Crimea, they did not act under the Russian flag and their actions were not officially recognised by Russia. Russian army in Crimea was disguised as “green men”—troops without insignia and no clear association with any state. Being wary of international and domestic response, Russia stood ready to engage its own army only if Ukraine gave it an appropriate opening. This was not the case. In the difficult conditions of the spring of 2014, the Ukrainian army refused to enter into conflict with an opponent without clear legal status—that is how the events that happened must be considered, in contrast to Russian propaganda.

In the spring of 2014, the Armed Forces of Ukraine were all but the army being downsized for more than 20 years. At short notice, the most operational units could provide only a third or, at best, a half of the elements provided for in the organisational structure. The weakest units were able to provide only pitiful force—a tenth of those they were supposed to operate. In order to ensure complete operationality, the army needed literally everything—operational vehicles, manpower, fuel, and organisational capabilities.

The very deployment of the Armed Forces in the combat area placed a heavy burden on them. Long-distance marches affected the tanks of the 1st separate tank brigade. The fire in Kryvyi Rih (most likely, it caught tanks which had been prepared for the march) prevented the formation of at least a single tank company. Add to this the explosion of two 2S19 SPGs of the 26th separate airmobile brigade, the downing of a Su-24M bomber in March 2014, and the breakdown of the entire BMP-2 battalion of the 28th separate mechanised brigade.

Still, despite a host of material, organisational and political factors of disorganisation, the Ukrainian army showed, most importantly, its intention to defend the state and respect for the oath. Ukrainian soldiers and officers managed to face the threat from Russia. Not being able to cover the entire border, the Armed Forces concentrated on protecting the most vulnerable areas. Defending the capital city from a rapid onslaught and preventing Russia’s possible advance to the Dnipro River were critically important.

The contents of the article are licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. Copyright exceptions are marked with ©.

The article was prepared with the assistance of the Ministry of Information Policy of Ukraine.

Підтримати нас можна через:

Приват: 5169 3351 0164 7408 PayPal - [email protected] Стати нашим патроном за лінком ⬇

Subscribe to our newsletter

or on ours Telegram

Thank you!!

You are subscribed to our newsletter