China’s rapid military buildup and Beijing’s increasingly aggressive behavior have made the PRC an unprecedented and most serious strategic challenge for Japan.

Over the past decade, China has dramatically expanded its armed forces. Its defense budget has more than doubled, reaching $213 billion in 2022. The size of its navy has grown by 60 percent, to 134 ships, while its combat aircraft fleet has also more than doubled, reaching 1,270 modern aircraft.

Japan’s capabilities are far more limited by comparison. Its defense budget stands at about $52 billion, with 72 major warships and 320 modern aircraft in service. Ten years ago, Japan’s Self-Defense Forces were able to compensate for their smaller size through superior technology and training. Today, however, China’s People’s Liberation Army surpasses Japan both in numbers and in overall capability – a reality Japan can no longer ignore.

Under these conditions, Japan is revising its defense doctrine and rapidly strengthening its military capabilities to repel a potential Chinese attack independently, even without immediate military assistance from the United States.

After World War II, Japan relied on its alliance with the United States as the cornerstone of its security (the so-called Yoshida Doctrine). Its Self-Defense Forces were constrained by a policy of “exclusively defensive defense” (senshu bōei), while the U.S. military presence was regarded as the primary “sword” in the region. However, the current strategic environment—especially the rise of China’s military power and North Korea’s nuclear threats—is forcing Japan to strengthen its independent defense capabilities. Concerns are also growing about a possible reduction in the U.S. role: Japanese experts note that the “America First” approach in the United States undermines confidence in the U.S. nuclear umbrella and Washington’s willingness to come to the aid of its allies.

According to specialists, relying on automatic U.S. intervention is risky. Japan, therefore, must prepare to operate under new conditions by building up its own ammunition stockpiles, strengthening its defense industrial base, and improving logistics.

In response to these challenges, the Japanese government adopted new strategic documents, the National Security Strategy and the National Defense Strategy, in late 2022. These documents explicitly state that China will remain Japan’s main strategic rival for decades to come and that the security environment surrounding Japan is the most severe since World War II. Japan plans a fundamental strengthening of its defense capabilities by increasing defense spending to around 2% of GDP (approximately ¥11 trillion per year by 2027) and developing new capabilities. The most significant shift is the decision to acquire so-called “counterstrike capabilities.”

This refers to the ability to strike enemy territory in response to an attack, including the destruction of the adversary’s missile launchers before new missiles can be fired.

This effectively amounts to the capability to attack enemy bases—something previously considered incompatible with Japan’s pacifist constitution. The government now justifies this shift as a matter of extreme necessity: to stop missile attacks on Japan, there may be no alternative other than preemptively striking the adversary’s launch systems (within the framework of self-defense and in compliance with international law).

Importantly, Japan views counterstrike capabilities as a tool of deterrence rather than an instrument of preventive war. The strategy emphasizes denial deterrence—dissuading an adversary by convincing it that an attack cannot achieve its objectives—rather than relying solely on punishment-based deterrence. Under the new doctrine, Japan will combine active defense (a multilayered missile and air defense system) with the ability to carry out retaliatory strikes, thereby undermining the aggressor’s “theory of victory.”

This approach is reflected in the concept of Integrated Air and Missile Defense (IAMD): the simultaneous interception of enemy missiles by enhanced missile defenses and synchronized strikes against launchers to reduce the intensity of attacks and deter further aggression. Official explanations by Japan’s Ministry of Defense explicitly state that the purpose of IAMD is to “intercept missile attacks with reinforced missile defense and possess counterstrike capabilities that deter the very act of launching missile attacks.”

Of course, even under the new doctrine, Japan does not envisage full autonomy from the United States – the alliance with Washington remains the cornerstone of its security. However, the emphasis is on ensuring that Japan can buy time and minimize damage using its own forces if, for any reason, U.S. intervention is delayed.

For example, war-game scenarios conducted by the CSIS in 2023 showed that in the event of a Chinese attack on Taiwan that draws Japan into the conflict, U.S. support would be decisive; without it, the chances of deterring China drop sharply. Understanding this, Japan seeks to make its contribution to deterrence as meaningful as possible so that, even without the direct involvement of American forces, an aggressor would suffer unacceptable losses.

Put simply, Japan’s new defense strategy is about increasing its “value as an ally” while also enhancing its ability to act independently during the critical initial phase of a conflict. Japanese analysts caution that relying solely on counterstrike capabilities as a panacea would be misguided: if China were to threaten nuclear escalation, whether Tokyo would dare to employ them remains an open question. Therefore, counterstrike forces are seen as a supplement to U.S. extended deterrence, not a replacement for it.

At the same time, efforts are underway to improve the resilience of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces – through the dispersal of bases, the construction of hardened shelters, and the stockpiling of fuel, energy resources, and ammunition – to withstand a prolonged conflict.

Japan’s missile defense system was developed starting in the mid-2000s in response to the missile threat from North Korea. It has a two-layer structure: a maritime layer comprising Aegis-equipped destroyers armed with SM-3 interceptor missiles to engage warheads in space, and a land-based layer consisting of Patriot PAC-3 batteries to intercept warheads in the terminal phase of flight.

At present, the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force operates eight Aegis destroyers equipped with SM-3 Block IA/IB missile interceptors (the Kongō, Atago, and the newest Maya classes). These ships patrol waters around the Japanese archipelago, tracking missile launches using powerful AN/SPY-1 radars.

The second layer consists of six Patriot PAC-3 air defense divisions deployed across the country and integrated into the JADGE command-and-control system.

In the event of a missile attack, Japan’s missile defense system operates automatically: first, Aegis/SM-3 interceptors attempt to destroy targets in the upper atmosphere, and if any warheads break through, Patriot PAC-3 systems protect key areas at about 20 km.

This multilayered system is being continuously upgraded. In particular, Japan and the United States have jointly developed the SM-3 Block IIA interceptor, which has a longer range and the capability to intercept intermediate-range ballistic missiles; it has been in service since 2018.

However, the rapid development of China’s missile forces poses extremely complex challenges for Japan’s missile defense. New threats have emerged that exceed the design limits of the current system, including hypersonic glide vehicles (HGVs), maneuverable warheads, and the sheer possibility of large-scale, synchronized launches of dozens of missiles capable of overwhelming defenses.

Japan’s Ministry of Defense acknowledges that “purely defensive means are insufficient” to cope with such challenges.

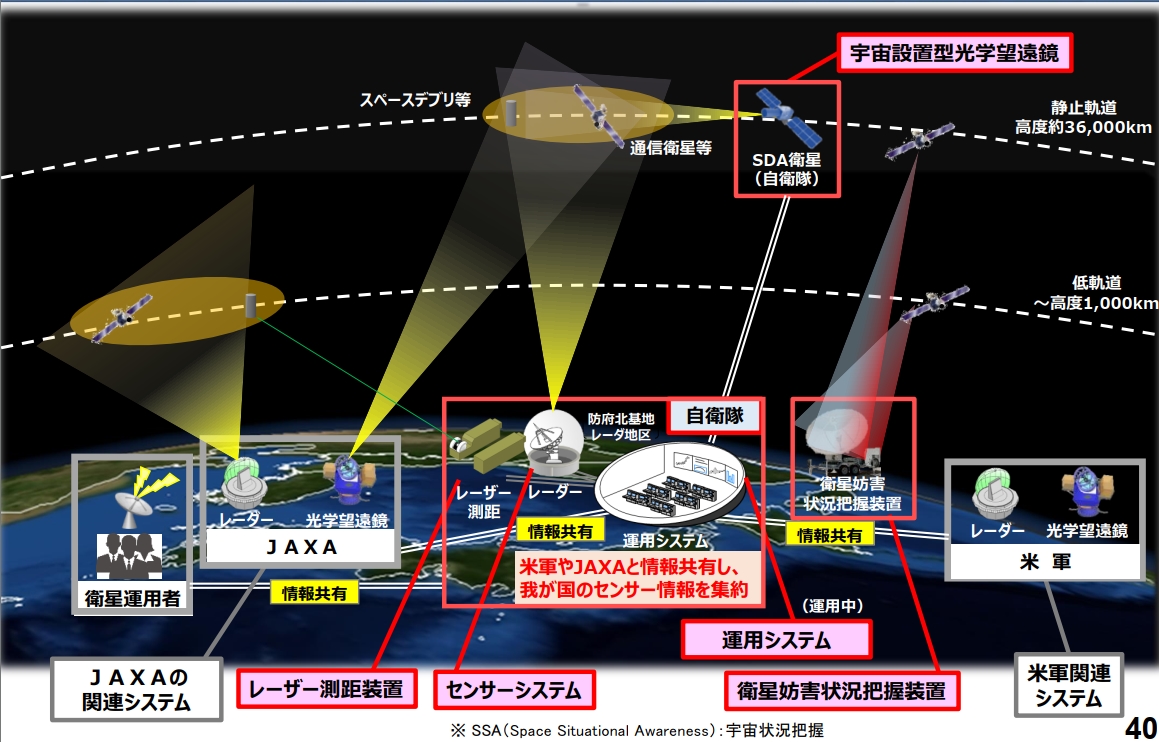

Therefore, first and foremost, Japan is modernizing its missile defense system itself. This includes installing new high-power active electronically scanned array (AESA) radars (such as the FPS-7), deploying a network of early-warning satellites to detect launches (with plans to launch constellations of small reconnaissance satellites for global monitoring), and developing next-generation interceptors. In particular, the medium-range Type-03 surface-to-air missile system is being upgraded to intercept HGV-type targets, and new ship-based interceptors, such as the GPI, are under development.

In parallel, Japan is investing in new missile defense technologies. Systems based on combat lasers and high-power microwaves are being studied to destroy targets at low altitudes – primarily to counter swarm attacks by drones or cruise missiles.

Second, Japan is increasing the number of missile defense platforms. In 2020, the deployment of the land-based Aegis Ashore systems was canceled due to technical and political difficulties. Instead, a decision was made to build two additional Aegis-equipped ships dedicated exclusively to missile defense (so-called “missile defense cruisers” with increased displacement). As a result, in the second half of the 2020s, the fleet of missile defense ships is expected to grow to 10–12 vessels, enabling simultaneous patrols in more directions and providing reserves for maintenance and repairs. Funding for these two ships was already included in the 2023 defense budget.

Despite Japan’s efforts, its missile defense system cannot yet fully protect the country against a potential Chinese missile strike. A massive salvo of hundreds of missiles could overwhelm the system. As the Ministry of Defense notes, even if the Self-Defense Forces were at 100% combat readiness 24/7, intercepting a simultaneous attack of roughly a thousand missiles would be practically impossible. Aegis and Patriot systems can destroy some missiles, but others would still reach Japanese territory.

Defense against cruise missiles is especially difficult. Unlike ballistic missiles, cruise missiles fly at low altitudes and can be launched in large numbers, while no dedicated defense system currently exists. Fighter jets and conventional air-defense systems could theoretically intercept them, but available forces would be insufficient against dozens or hundreds of targets.

To address this, Japan has introduced counterstrike capabilities: the ability to destroy some missiles on the ground before they are launched. This approach reduces the load on the missile defense system and increases the chances of intercepting remaining targets. By the 2030s, Japan plans to develop a fully Integrated Air and Missile Defense (IAMD) system, combining the “shield” (interception) with the “sword” (counterstrike). This ensures that any missile attack would trigger retaliatory strikes against launch sites, while some missiles are intercepted, making a successful attack unlikely.

Currently, Japan has eight Aegis ships (SM-3) and six Patriot PAC-3 batteries, integrated into a single system. By the end of the decade, the fleet is expected to grow to 10 Aegis ships with next-generation interceptors, upgraded Patriot batteries, new radars and satellites, and strike missiles as part of the missile defense system. This marks a significant improvement compared to the previous decade, aimed at countering the growing missile threats from China and North Korea.

Japan’s air defense is closely integrated with its missile defense system, but has its own distinct focus. Air defense is designed to counter enemy aircraft, cruise missiles, and drones. Its core components are the Japan Air Self-Defense Force’s fighter aircraft and a multilayered network of ground-based surface-to-air missile systems.

As of 2025, Japan has approximately 260 operational combat aircraft (with additional aircraft in reserve or training units). This primarily includes F-15J/DJ interceptor fighter jets (around 200 in total, with roughly 150 in active units), multirole F-2A/B fighter jets (about 90), and the latest F-35A stealth fighters (39 as of March 2025). Japan is actively modernizing its fleet: the old F-4s have been retired, about half of the F-15Js are planned to be upgraded to the JSI version with new radars and missiles, and, most importantly, Japan is procuring 147 F-35s (105 F-35A and 42 F-35B short-takeoff variants).

This number will make Japan the second-largest F-35 operator in the world, after the United States. F-35A fighters are already deployed at Misawa and Komatsu air bases, while F-35B aircraft are expected to enter service from 2025, intended for operation from the modernized Izumo-class helicopter carriers.

To detect air attacks, Japan operates an extensive network of radar stations and AEW aircraft. Dozens of long-range radars (FPS-3, FPS-5, FPS-7 types) are positioned along the coastline, creating continuous radar coverage. The Air Self-Defense Force also fields four E-767 AEW&C aircraft and 20 smaller E-2C/D Hawkeye aircraft. These platforms regularly patrol the airspace, especially during periods of heightened tension, and can detect approaching targets well in advance. Once a target is identified, interceptor fighters from alert units are scrambled to engage.

In peacetime, air defense forces maintain constant readiness at key air bases (Chitose, Hyakuri, Komatsu, Nyutabaru, and Naha) to cover their respective regions. In wartime, the plan is to launch the maximum number of aircraft and disperse them to alternate airfields, including civilian airports, to protect assets from missile strikes.

However, there is a vulnerability: most Japanese air bases lack reinforced shelters (hangars are not protected with concrete). In the event of an attack on the airfields, fighter jets left on the ground could be destroyed. The Ministry of Defense notes that the lack of protective shelters, combined with the absence of a civilian defense system, leaves Japan vulnerable—missile strikes on bases or infrastructure could cause significant losses.

In addition to aircraft, Japan’s air defense includes surface-to-air missile systems of various ranges. The longest-range system is the U.S.-made Patriot PAC-3, which, in addition to missile defense, can intercept aircraft and cruise missiles, with an effective range of approximately 20–30 km against aerodynamic targets. Patriots protect the Tokyo metropolitan area, major cities, and key bases.

The second layer consists of Japan’s medium-range Type-03/Kai Chu-SAM missiles, with ranges of approximately 60–120 km, currently deployed in 23 batteries and planned to increase to 29. These mobile systems cover gaps between Patriot batteries, protecting landing zones, troop concentrations, and other key areas. There is also a new short-range Type-11 system (about 15 km), which replaces the older Type-81 and is deployed with both air and ground forces.

Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force ships are equipped with RIM‑162 ESSM surface-to-air missiles (with a range of up to 50 km) and RAM systems (up to 10 km), which provide close-in self-defense for ships. This multilayered air defense network allows targets to be engaged from high altitudes down to extremely low levels. However, fighter aircraft still play the key role, as they can patrol far from the coast and destroy missile carriers before launch.

One of the main directions in Japan’s air defense development is improving its ability to counter simultaneous large-scale air attacks, reflecting the growing threat from China. At present, the number of surface-to-air missile systems and alert fighters is limited. In the event of a large-scale attack from multiple directions, available resources could be exhausted. Cruise missiles and drones are of particular concern: they fly at low altitudes and can be launched in large numbers, while Japan’s air defense is not yet fully adapted to such threats. In a “first wave” of hundreds of cruise missiles, the Self-Defense Forces would be physically unable to intercept all fighters, and SAMs would destroy some, but others could still reach their targets.

This is why projects involving combat lasers and high-power microwave systems have emerged, as they could simultaneously engage entire “swarms” of targets. Their deployment is planned for the 2030s. At the same time, Japan is already acquiring advanced air defense weapons, including the SM‑6 missile, which is being deployed on Aegis-equipped destroyers and can engage both ballistic missiles and low-flying targets at ranges of 200–250 km.

Japan, as a maritime nation surrounded by water, places high importance on sea-based defense and anti-ship capabilities, especially in the event of a conflict with China. Beijing could potentially use its navy to blockade Japan or attempt a landing on Japanese islands—particularly the disputed Senkaku Islands or the southern Nansei Islands. To prevent this, Japan deploys powerful asymmetric systems, including coastal and aerial anti-ship missile (ASM) units.

On land, Japan has established specialized coastal defense missile units. ASM batteries are already stationed on Okinawa, Miyako, and Amami islands. Notably, in 2023, a unit equipped with missile systems began deployment on Yonaguni Island (the westernmost island, just 110 km from Taiwan), despite Chinese protests claiming “increased tension.”

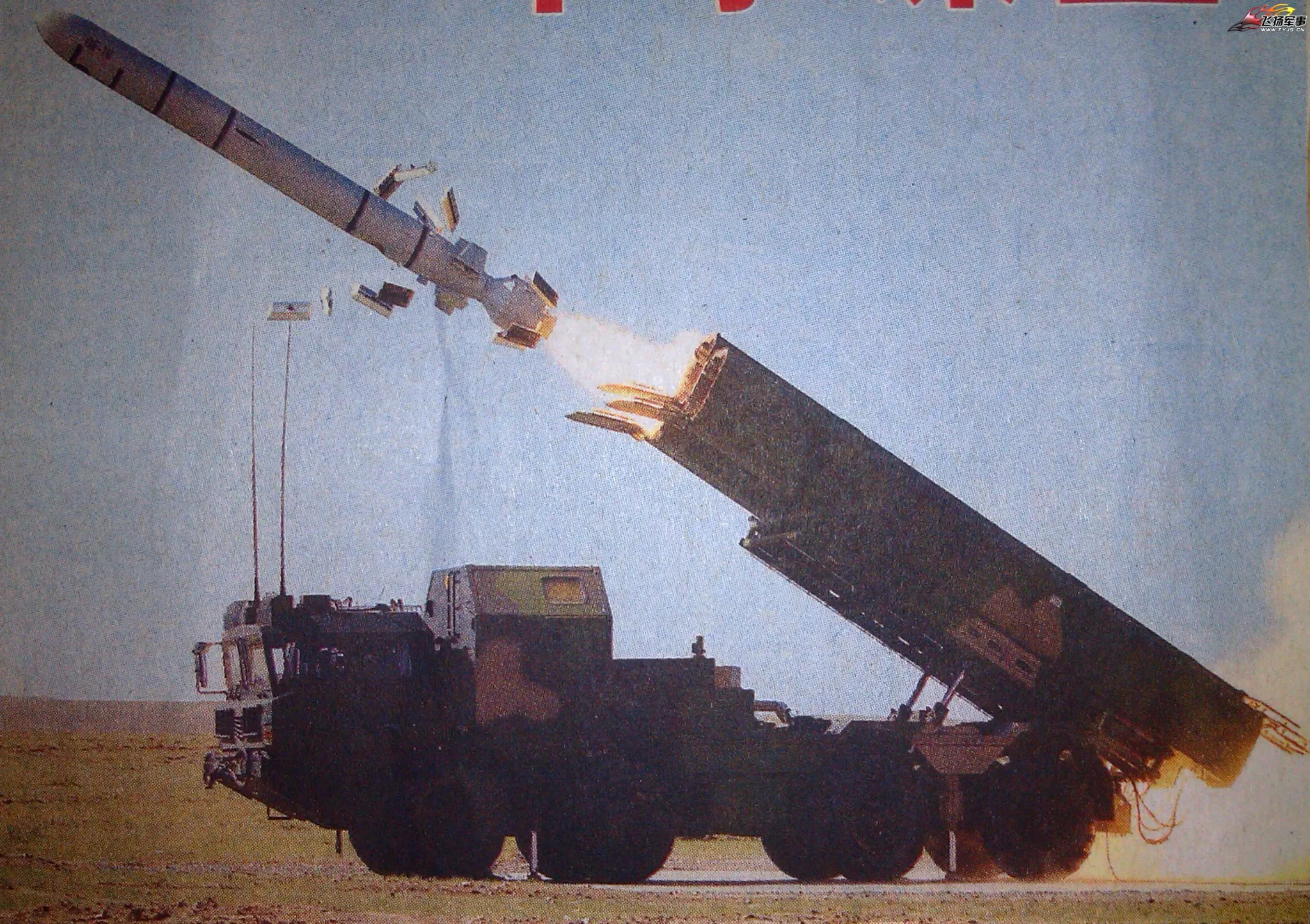

The primary weapon of these units is the Japanese Type-12 cruise missile. This modern missile has a range of approximately 200–250 km, high accuracy, and an active radar seeker. It is launched from mobile truck-mounted launchers, which are easy to conceal or relocate. Currently, the Type-12 can strike ships within the East China Sea, and Japan has deployed a total of 22 Type-12 batteries.

In response to China’s deployment of longer-range missiles, Japan has decided to dramatically extend the range of its anti-ship missile systems. A modernization program is underway to upgrade the Type‑12 missile in its land-based, ship-based, and air-launched versions to a range of 1,000 km or more. In effect, this will turn the Type‑12 into a universal long-range “standard” missile, suitable for striking both naval and land targets. The upgraded missiles are expected to enter operational service starting in 2026. This urgency reflects Japan’s desire to field its own long-range anti-ship missiles before China completes the modernization of its navy.

In addition to the Type‑12, Japan still operates the older Type‑88 anti-ship missile (with a range of about 150 km), which is gradually being phased out in favor of newer systems.

Aviation also plays a critical role in anti-ship defense. In particular, Japan has developed the highly capable F‑2A fighter-bomber, which can carry up to four anti-ship missiles such as the ASM‑2 and ASM‑3. The ASM‑2 is a Japanese air-launched anti-ship missile with a range of around 170 km, while the ASM‑3 is a new high-speed supersonic missile capable of reaching Mach 3, making it harder to intercept. Its range is up to 400 km. These missiles are intended for use by F‑2 aircraft to engage Chinese naval vessels in the event of an invasion threat.

It is also worth noting that Japanese maritime patrol aircraft (P‑3C and the newer P‑1) are armed with Type 91 lightweight anti-ship missiles, enabling them to engage both surface and subsurface targets.

Finally, every destroyer and frigate of the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force is equipped with shipborne anti-ship missiles—primarily the Type‑90 (the naval version of the Type‑88), with 4–8 missiles per ship. In addition, Japan is currently transitioning from the Type‑90 to the more modern Type‑17 missiles, which are derived from the land-based SSM‑2 missiles of the Type‑12 family. As a result, if the Chinese navy approaches Japan’s shores, it could face crossfire from land, air, and sea.

A key element in strengthening Japan’s anti-ship defense has been the creation of the Amphibious Rapid Deployment Brigade (ARDB)—essentially Japan’s marine corps. Its missions include preventing the seizure of remote islands and, if necessary, conducting counterattacks to retake occupied territory. The ARDB brigade (about 3,000 personnel) was formed in 2018 on Kyushu, and is equipped with AAV7 amphibious assault vehicles, MV‑22 Osprey tiltrotor aircraft, and other assets. In the event of Chinese aggression, Japanese marines are expected to rapidly deploy to threatened islands to hold them or expel enemy forces.

These forces are supported by the aforementioned coastal missile units, together forming an anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) zone across the southwestern islands. Japan’s Ministry of Defense has openly stated that it will continue to develop standoff defensive capabilities to strike enemy ships and landing forces from a safe distance. This includes not only missiles, but also naval mines, anti-ship aviation, and submarine forces – everything necessary to prevent hostile landing forces from approaching Japan’s shores.

As noted earlier, Japan has decided to acquire its own long-range strike weapons capable of hitting targets on enemy territory—primarily Chinese missile bases and command infrastructure. First, Japan has ordered U.S. Tomahawk cruise missiles. In 2023, Tokyo announced the purchase of 400 Tomahawks with a range of about 1,600 km. Deliveries will begin in 2025, one year earlier than initially planned. Japan will first receive 200 Block IV missiles, followed by 200 of the newer Block V variant. These missiles will be deployed on Aegis-equipped destroyers, including the Chōkai, giving the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force its first-ever long-range land-attack capability.

Second, Japan is upgrading its indigenous Type‑12 missile family. In addition to anti-ship missions, the modernized Type‑12 will be able to strike fixed ground targets, such as missile launch sites and command centers. With a range of over 1,000 km, these missiles can reach coastal regions of mainland China when launched from Kyushu or from ships in the East China Sea.

Third, Japan is developing hypersonic weapons. Work is underway on a Hypersonic Glide Vehicle (HVGP) for coastal launch systems, designed to fly long distances and penetrate enemy missile defenses. Testing is scheduled for 2025–2028. These weapons are intended to defeat heavily defended, high-value targets.

In addition, starting in 2026, Japan will begin deploying ballistic missiles equipped with hypersonic glide vehicles (HVGP Block 1), which are classified as short-range ballistic missiles. By 2030, a Block 2 version with a range of up to 4,000 kilometers is expected to enter service.

Japan is also procuring other foreign weapons systems, including air-launched missiles such as JASSM and JSM to arm its F‑35 fighter jets. Overall, the goal is to field several hundred domestically controlled missiles with ranges exceeding 1,000 km by the early 2030s, enabling Japan to deliver a meaningful counterstrike in response to aggression.

Undoubtedly, Japan’s counterstrike forces remain far smaller than China’s (hundreds of missiles versus thousands). However, for deterrence purposes, the mere existence of this capability matters.

Some Japanese researchers openly describe worst‑case scenarios. For example, military analyst Atsunobu Kitamura, writing for Asahi GLOBE+, introduced the concept of a “short lightning war” conducted by China. According to his analysis, Beijing is preparing the capability to launch a sudden, devastating missile and air campaign against Japan to paralyze its will to resist within a matter of days.

Kitamura notes that China has accumulated around 2,000 short‑ and medium‑range ballistic missiles and more than 2,500 cruise missiles, which he describes as “ideally suited for strikes against Japan.”

If ordered, China could launch a single massive salvo of 150–200 ballistic missiles and 700–800 cruise missiles against key targets, including power plants, transformer substations, radar sites, oil storage facilities, and government centers. In Kitamura’s assessment, such an attack would turn territory from Okinawa to Hokkaido into a zone of devastation, disabling critical infrastructure. Even the most advanced missile defense system, he argues, would be unable to cope with an attack of this scale.

China’s goal is to break Japan’s will to resist without a direct invasion, forcing capitulation under the threat of further destruction. This approach aligns with the Chinese concept of “winning without fighting,” inherited from Sun Tzu. According to the Japanese expert, the only way to deter such a strategy is to show China that it will not work. This requires either:

As Kitamura acknowledges, Japan currently lacks a comprehensive response to the threat of a “short war,” beyond relying on U.S. assistance. Meanwhile, the United States is only beginning to build up its own missile forces in the region following its withdrawal from the INF Treaty. This “vicious circle” means that the next few years, up to around 2030, constitute a critical period during which China may enjoy a window of military opportunity.

To better understand the scale of the threat, it is crucial to examine the main strike assets China could use against Japanese territory. These primarily include:

In recent years, China’s armed forces have made significant progress in all of these areas, significantly strengthening their capacity to conduct offensive operations in the region.

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) possesses one of the world’s largest arsenals of short- and medium-range ballistic missiles. China’s Rocket Force, in particular, fields the following systems:

In addition, China fields intercontinental ballistic missiles (DF‑31, DF‑41) with nuclear warheads intended for strategic deterrence against the United States. These systems would likely not be used except in extreme circumstances, due to the risk of nuclear escalation.

A second major threat to Japan comes from long‑range cruise missiles launched from land, sea, and air platforms. China has developed a broad family of such weapons, broadly comparable to U.S. Tomahawk missiles. The most well-known is the Changjian‑10 (CJ‑10), also known as Donghai‑10 (DH‑10) in its land‑based version. This is a subsonic, low‑flying cruise missile that follows the terrain, with a range of approximately 1,500–2,000 km and a ~500 kg warhead(high‑explosive or cluster). Its high accuracy with a circular error probable of just 5–10 meters allows it to destroy even point targets, such as an aircraft hangar or a command center.

According to estimates, China possesses at least 500 such missiles in various modifications. Under the PRC’s military doctrine, CJ-10 missiles could be used for precision strikes against critically important targets on Japanese territory – government buildings, power plants, petrochemical facilities, missile defense radars, and the like. Their accuracy enables destroying targets with maximum effectiveness using a minimal number of launches.

In this regard, analysts predict that in the event of an attack, up to 70% of the Chinese salvo could consist of cruise missiles, with only 30% being ballistic missiles. This would allow the number of launches to increase severalfold, since cruise missiles are cheaper to produce, smaller in size, and easier to conceal.

As of today, Japan recognizes the scale of the military threat from China and is undertaking a historically unprecedented buildup of its defense forces. The main goal is to create, by the early 2030s, an army capable of fighting off the first wave of an attack on its own (or with minimal allied support), protecting the lives of citizens and critical infrastructure, and inflicting sufficient damage on the aggressor to halt further aggression.

At the same time, Japan demonstrates its commitment to a purely defensive doctrine—all measures fall within the framework of self-defense and deterrence. This is an important signal for both domestic and international audiences: Tokyo does not seek an offensive war.

Given China’s rapid military growth, the arms race is likely to continue. However, as Japanese leaders emphasize, strong defense is the guarantor of peace: only by making potential losses unacceptable for China can aggression be prevented.

Japan, while refusing to “fight for others’ interests,” clearly demonstrates its readiness to defend its own land at any cost. This is precisely the key deterrent signal to Beijing in the near term.

Підтримати нас можна через:

Приват: 5169 3351 0164 7408 PayPal - [email protected] Стати нашим патроном за лінком ⬇

Subscribe to our newsletter

or on ours Telegram

Thank you!!

You are subscribed to our newsletter